At 4 PM on the 29th of October 2019, Saad Hariri resigned as Prime Minister of Lebanon. But how did we get there, and more importantly, where do we go from there? In this post, I follow the Lebanese October Revolution day by day, event by event, trying to decipher how a tax protest grew into a nationwide revolution, brought down a government, shook an entire political class out of its throne, struggled with a counter-revolution, and eventually massively changed the well-established common-sense rules of the Lebanese politics.

This blog post is a diary that covers the first two months of the October Revolution and all of Lebanon’s political developments from the 17th of October till the 20th of December.

Thursday, October 17 – Day 1: The Tax that Broke the Camel’s Back

On the 17th of October, Lebanon was a country on the verge of a financial crisis. A country whose currency had begun an unofficial devaluation. A country where bakeries and gas stations had been threatening to go as well as going on strikes for three weeks. A country where wildfires had ravaged what remained of Lebanon’s forests over 48h due to the lack of equipment maintenance. A country that was extremely mismanaged over the past 3 months, and not managed at all for a good duration of the past decade. So when on the 17th of October 2019 news got out that the government was about to add a new tax on Whatsapp voice calls as part of the new austerity measures for the 2020 budget, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and sporadic protests quickly spread across Lebanon, with massive crowds gathering in Beirut, Tripoli, Jounieh, Akkar, and almost everywhere in the country. As scuffles broke out between riot police and a number of protesters in Martyrs’ square in Beirut, bodyguards of education minister Akram Chehayeb fired shots in the air in the evening as they clashed with protesters in Downtown Beirut, only adding fuel to the fire. The importance of that moment came through a photograph, which has since been re-imagined in cartoons, sketches and paintings, in which a Lebanese woman is seen karate-kicking one of Chehayeb’s armed bodyguards in the groin, forcing him away from protesters: What was about to become the 2019 October revolution had just created its first icon. As the protests kept going that night, Chehayeb announced that the schools and universities would be closed on October 18, while minister of telecommunications Mohamad Choucair announced that the Whatsapp tax would not be implemented, as Hariri made it clear that cabinet would meet the next day to discuss reforms.

But it was too little, too late.

Friday, October 18 – Day 2: The Great Strike and the Greater 72 Hours

In a country in which most syndicates are either dysfunctional or under political control, It is not that easy for a strike to work. Yet on the 18th of October 2019, Lebanon woke up for the first time in years to the sight of protesters blocking roads everywhere around the country, from Beirut and its southern and eastern suburbs, to Mount-Lebanon and the Bekaa, to Saida and Tripoli and the North . Tripoli burst in anger when one of the bodyguards of former (pro Hariri) MP Mosbah Ahdab opened fire on protesters, so when news broke out that in the southern districts – unarguably a stronghold of Amal and Hezbollah with up to 90% of votes in approval for their joint lists in the 2018 parliamentary elections – citizens were destroying the offices of Amal and Hezbollah MPs, the decentralized anti-tax movement quickly turned into a national stand by citizens who finally spoke and resisted the oppression of their Zaims. For the first time in the history of Lebanon, an anti-elitist cross-sectarian sentiment had united most of the fragmented country against its leaders.

The strike paralyzed everything around Lebanon, and the fact that the minister of education had postponed classes in universities and schools around the country the night before, made it even more possible for people to participate in the protests. So when anti-riot police were clashing with the protesters in downtown Beirut (and then arresting them before releasing them under pressure the next day), FPM MP for Jezzine Ziad Aswad arrogantly tweeted on the night of the 18th of October that he could now get to his Yacht in Beirut. The FPM had clearly not understood that one of the key catalysts of the protests was the arrogance of a political class that no longer took shame in its mismanagement and institutionalized theft. You can say that Ziad Aswad didn’t eventually get to his Yacht the next day (he afterwards denied its existence), while an anti-Gebran Bassil chant eventually quickly became the unofficial anthem of the protests.

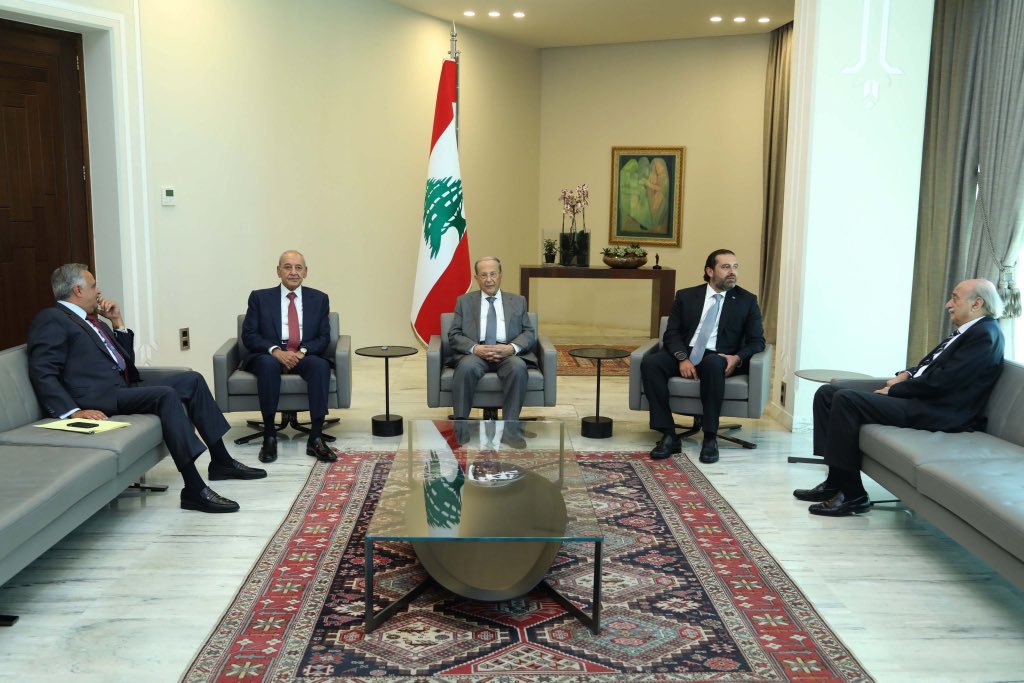

Hariri, who had called for an emergency cabinet meeting that day, eventually cancelled that meeting, and gave a speech from the Grand serail in which he asked the protesters for 72 hours for him and the political parties to find a solution for the crisis. Hariri, in his effort to throw the collective blame on his entire cabinet, indirectly weakened himself as premier by cancelling the cabinet meeting and showing himself as uncomfortable with waves of protests, gave 72 hours of reasons for protesters to stay in the streets – including a Monday, the third day, which was the beginning of another week – and confirmed the inevitable: He made the protests look like a cross-sectarian movement against a coalition of ineffective corrupt Zaims (leaders). The political class could have fought the movement since its beginning by showing them as a protest that was meant for a particular politician/sect or not another, but their choice of holding out together (in the spirit of continuing the status quo of institutionalized stealing) and avoiding sowing sectarianism in their stances (at the very beginning) galvanized the protest and turned it from decentralized riots into a revolution against the entire political class in less than 72 hours – a revolution so decentralized than Lebanese immigrants throughout the world started organizing anti-establishment protests almost everywhere.

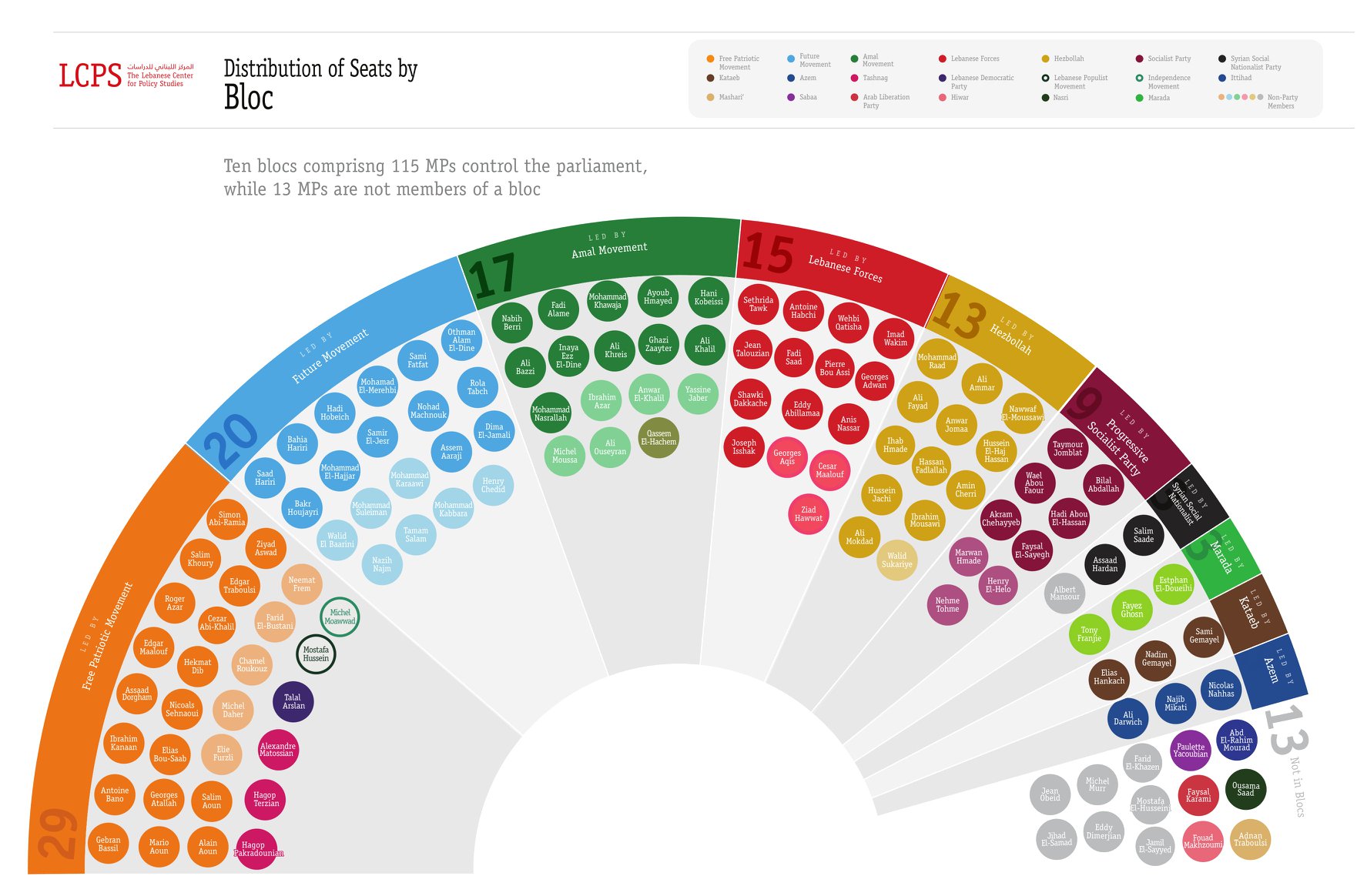

Saturday, October 19 – Day 3: Infiltration Through Anti-Resignation and Resignation

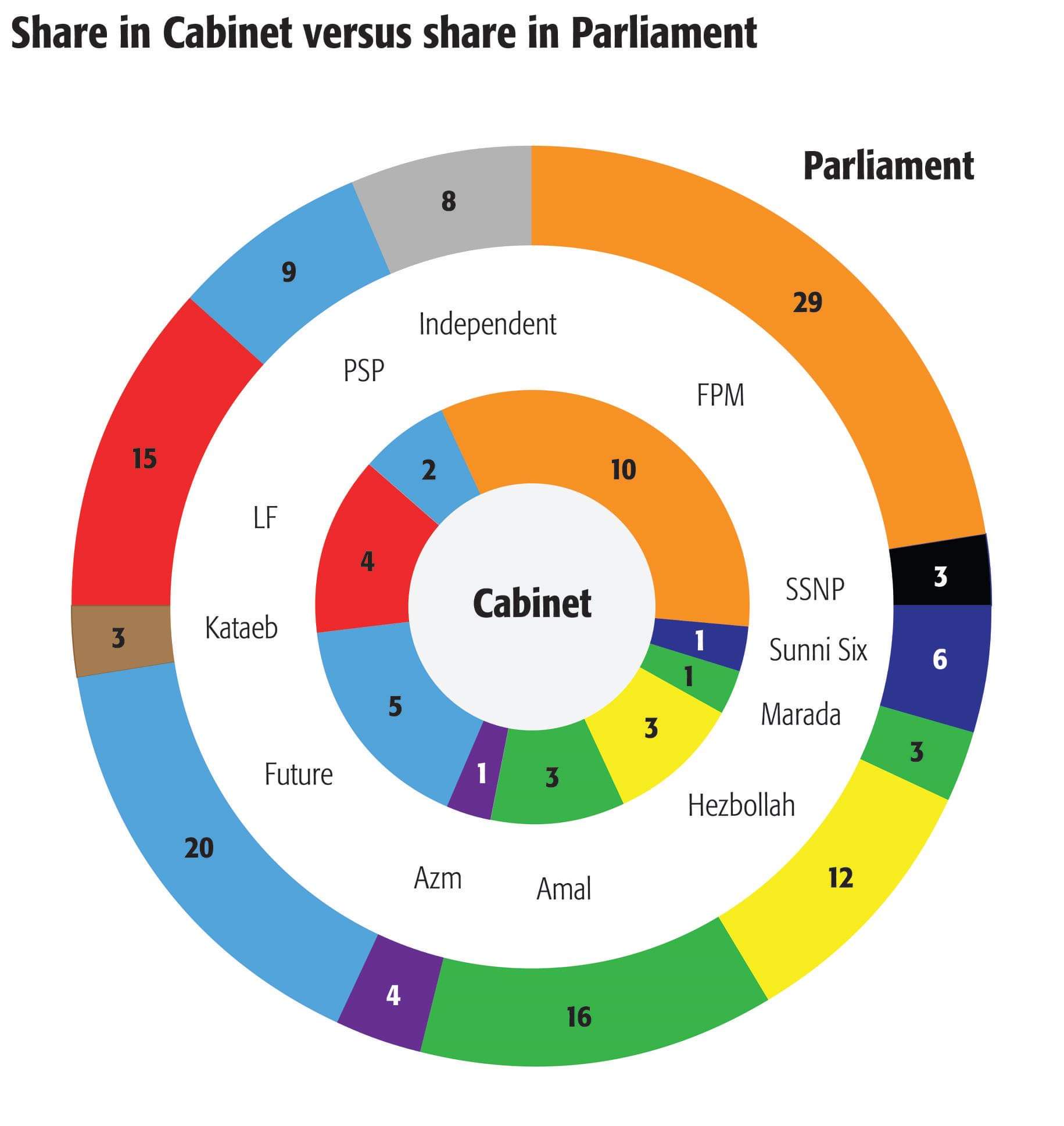

Only Geagea, as politically unskilled as he is, quickly saw the danger of uniting the entire political class in the face of widespread popular anger. As a political party, the Lebanese Forces had the least to lose from leaving the coalition: Aside from the symbolic position of deputy PM, they had no real influence in the cabinet: With only 4 votes out of 30 compared to the FPM’s blocking third, it was almost impossible to block any decision from happening especially that Hariri had been getting closer to Bassil in the past couple of months and that it was without any question a pro-Hezbollah cabinet (with pro-Hezbollah ministers – everyone except for occasionally the FM and the PSP, and the LF – accounting for two-thirds of the ruling coalition). It was as well the FPM’s cabinet, with 10 Aounist ministers holding among other portfolios the key ministries of defense and foreign affairs, under the command of Bassil and the supervision of a President who is Michel Aoun himself.

Meanwhile, on the 19th of October, and while pro-Amal thugs where doing their best to squash the protests in the South (mainly in Tyre), Hezbollah’s secretary general finally took a stance from the protests that had been ravaging the country for the past 3 days. In his speech, in which he defended the Lebanese cabinet, he called against its resignation – which was a popular demand from the protesters – while threatening that a new government formation could take time, up to a year or two, trusting the 2018 Hariri cabinet to come up with economic reforms. After all, Hezbollah had not had a cabinet so loyal to him in 6 years, and the party of God had been enjoying that privilege even more through the presence of Hariri as head of the government. In that sense, any blow to the cabinet – be it from the streets or from within – would be seen as a blow to Hezbollah as well as its allies across the political spectrum. In defending the government, Nasrallah’s speech did not resonate well as he put himself in the same ditch as all the political class, standing for its decisions, and undermining all previous statements from Hezbollah that the party of God was doing its best to fight corruption.

Aside from participating in the institutionalized pie-sharing in cabinet, the Lebanese Forces had absolutely no reason to be part of a hostile cabinet – The LF were the only party in cabinet that was so-openly anti-Hezbollah, with the PSP and the FM fluctuating in their stance depending on the situation. So when an anti pie-sharing revolution kept going strong for the third day with blocked roads and more organized protests everywhere in the country, against an officially (after Nasrallah’s speech) Hezbollah-backed cabinet, it was the logical move from Geagea to instruct his ministers in the cabinet to resign from the government on the night of the 19th of October in a bid to gather political support and ride the wave.

Ironically, it would be naive to think that Hezbollah and the FPM did not benefit as much as LF from their resignation. For the Lebanese politicians who had fallen into the trap of finally rightfully showing themselves as single ruling oligarchic class, the official rift in the ruling coalition made it possible for them to finally politicize the protests: The LF would join the revolution in a common goal to bring down the rest of the parties (notably the FPM), and Hezbollah as well as the FPM through their media outlets had finally found a culprit to blame the protests on. As much as it didn’t make sense, OTV as well as other pro-Hezbollah media outlets to pin the entire revolution on the LF, and had found a way to sow discontent between protesters by trying to show it as a pro-Hezbollah vs. anti-Hezbollah issue, reorienting the entire protests into the traditional March 8 vs March 14 divisions. The cyber-war by pro March 8 media outlets that the protesters were mostly LF members trying to weaken the rule of the FPM could now finally make some sense – provided you’re willing to convince yourself that Geagea is able to mobilize tens of thousands of Shias and Sunnis in the Beirut, the Bekaa, the South and the North.

Sunday, October 20 – Day 4: They Say the War Is Over if You Really Choose

Yet again, the late afternoon and night moves by the political class to bicker among themselves on the 19th of October in order to reduce the intensity of the protests were too little and too late, backfiring on the 20th of October. Bolstered by a weak prime minister, a fractured government, the Lebanese forces joining the anti-regime protests, the collapse of the barrier of fear in regions where political repression was previously the norm, the quick and inappropriate return of official (by the anti-riot police in Beirut) and unofficial repression (by pro-Amal thugs in the South) as well as a stupid political class that chose to stick together in literally the only moment when it shouldn’t have, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese abandoned their allegiances to their Zaims and took to the streets of the country to make their voices heard. According to some estimates, the number of Lebanese who mobilized against their leaders in all of the decentralized protests across the country would be more than a million – the largest protests in Lebanese history (at least since 2015). For the first time ever, many Lebanese abandoned their sectarian allegiances and fears that date to the civil war, criticizing the Zaims and the government that represents them all, calling them corrupt, cursing them, and requesting a change in the way the country has been managed for the past 30 years by the establishment.

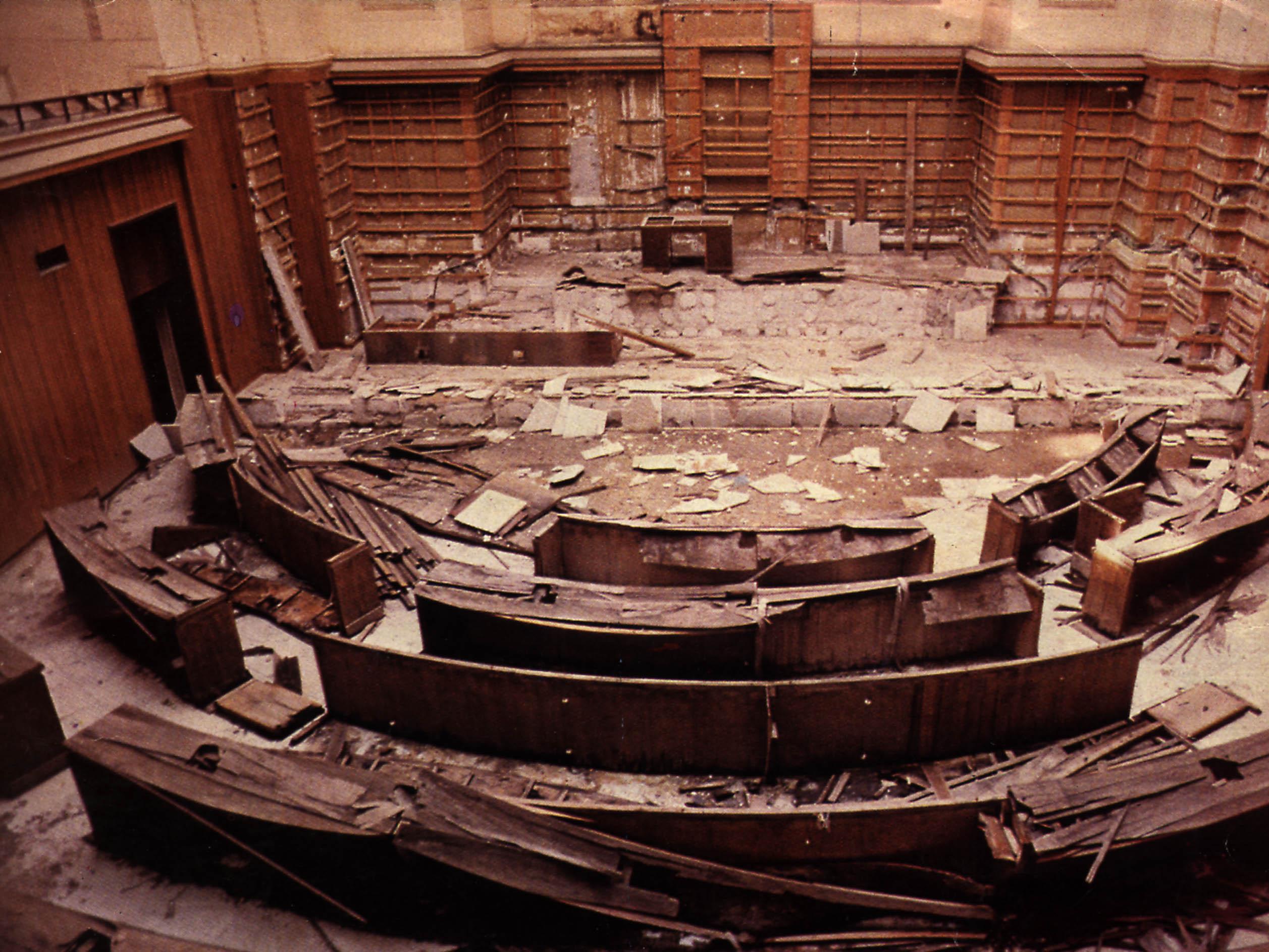

For the first time in Lebanon’s modern political history, the political class had officially lost its grasp on the people. On the 20th of October 2019, the Lebanese embraced each other and finally ended their leaders’ civil war that has been ongoing since 1975 as well as the artificial peace between the Zuamas that dates to 1990. They say the war is over if you really choose, and on the 17th of October, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese chose to end the war among themselves, a war that has been artificially implemented by their leaders, turning the tables and uniting against the establishment. In less than 4 days, a riot over a Whatsapp tax had somehow turned into an anti-establishment revolution.

Monday, October 21 – Day 5: 72 Hours and 22 Items

Lebanon woke up on the fifth day of the revolution to news of a strike that was still ongoing as well as roads that were still being blocked. The cabinet had probably hoped that a protest fatigue would slowly cripple the strike, but Hariri’s 72 hour deadline only made people mobilize more, and gave everyone an alibi to keep the strike and nationwide protests ongoing for another week. In his speech on Friday, the Prime Minister had indeed made it look as if his resignation was a possibility, encouraging people to protest even more. The absence of any kind of protest fatigue put immense pressure on the cabinet that met for several hours, eventually coming up with a reform paper that Hariri announced on the afternoon of the 21st of October. It included 22 items, with several ones destined to be popular with the masses (such as cutting the salaries of MPs and ministers by 50%, healthcare for the elderly) and others that are far, far from realistic (such as reducing the budget deficit to 0.6% without adding any new taxes), also miraculously coming up with a budget in 72 hours when they had a heavy history of procrastinating for months – The 2019 budget was passed in July, several months after it was supposed to be voted. All in all, the reform package proposed by the cabinet was a farce that was intended to seduce the Lebanese with answers to some popular demands, without proposing any viable solutions (Jad Ghosn’s 15 minute video breaks down how unpractical and unrealistic the reform package is).

If anything, the amount of work the government did and promised to do under pressure made everyone wonder: If so much was done in 3 days and so little time, what on earth has the political class been doing during the past 30 years? In its quest to control popular anger, the establishment had indirectly made everyone realize how powerful the threat of accountability was. So as protesters throughout the country chose to stay in the streets, the revolution had survived another obstacle: False promises.

With the failure of its carrot strategy, the establishment resorted again on the night of the 21st of October to the stick: Videos circulated across social media of men on motorcycles hoisting Hezbollah and Amal Movement flags attempting to infiltrate the protest in Downtown Beirut before the Army stopped them and forced some to flee.

Tuesday, October 22 – Day 6: Pressure from the Banks and on the Media

As the protests and the strike kept going for the 6th day, the country’s banks took the decision to remain closed – they would stay closed until the 31st of October. The rumor on the ground was a major concern that the reopening of the banks would lead many to withdraw their money and a subsequent economic collapse. In practice, however, the closure was an additional pressure tool on protesters who didn’t have an easy access to their finances and who couldn’t get their paychecks. Whether intended or not, the banking closure became yet another useful tool from the establishment to force the people to get out of the streets. For a revolution that blamed Riad Salameh’s Banque du Liban for the financial crisis that led to the protests, it wasn’t perhaps the best idea in the world for the banks to put themselves in the firing line even more: On the 22nd of October, the demonstrations eventually made it to BDL.

But the pressure from the banks was not enough, and the establishment – that effectively controls in a way or another, directly or indirectly every single media outlet out there – decided to take full control of the country’s official news outlet, the National News Agency (NNA), as minister of information Jamal Jarrah of the FM – ironically a ministry his boss took a decision to dissolve only 24 hours earlier as part of his reform package – took the decision of replacing the head of the NNA with a pro-Bassil figure.

Truth be told, the NNA usually never takes sides in the political developments, but is crucial in the objective reporting of the boring stuff (X met Y and Z happened in A). If you’re a politician who’s threatened of being ousted by a revolution, do you really want the people to know that Z is happening in A via the state’s outlets, while your own media outlets are already doing their best to propagate false rumors and discredit the uprising in every single way?

So through misinformation, fake news, different narratives and fear-mongering, the media war on the revolution had officially begun.

Wednesday, October 23 – Day 7: The Great Roadblock of Jal El Dib

On the 23rd of October, as the strike and the protests were still ongoing, the ruling class took the very intelligent decision of opening the roads by force against the demonstration mid-week instead of letting it die out – mind you, this is sarcasm.

Probably in an attempt to politicize the nature of the protests, two major attempts were made to open roads: The first one was in Zouk – a protest site that had naturally attracted more Lebanese Forces partisans, while the second one was in Jal El Dib, a protest site that had naturally attracted more Kataeb partisans (due to its location in the Metn). The protesters, who usually faced off with the ISF and anti-riot police, had this time to deal with the army itself. In Jal El Dib, Sami Gemayel of the Kataeb tried to join the protesters in their quest to keep the road open, while in Zouk, FPM MP Neemat Frem also took to the streets to calm tensions. Both were booed and eventually left the protest site while the protesters had successfully kept the roadblock of Jal El Dib closed. Elsewhere in the south, an attempt to forcefully open a road in Saida led to injuries among protesters.

The decision to open roads only galvanized the protests more, when the strategy of letting them die out on their own was proven to work in August 2015. The move was also another decision by the ruling class to frame the protests as anti-FPM revolution, by focusing on two regions that had a higher LF and Kataeb number of protesters. It was important for the Aounist media to portray the strike and roadblocks as an attempt to undermine them by the LF (who had just resigned from cabinet) and the Kataeb (who have been outside the cabinet since 2016), because the only alternative for the Aounists would be to admit that it was a nationwide revolution against the Ahed (that translates into the “Covenant”, or العهد), the word the FPM uses to represents the rule of Michel Aoun. The FPM had the most to lose from the resignation of the cabinet (10 ministers, key ministries and majority through their allies). The resignation of the government would weaken the FPM and send a message that three years into the Ahed, they had failed and were directly responsible for a failure that they only had recently enabled but that the entire political class was to blame for. The resignation would also weaken Bassil – who infamously became one of the major symbols of the revolution through the trademark Helahelaho chant – at a time when Bassil had recently intended to go to Syria to do presidential business, hoping to replace his father in-law after Aoun leaves power. Which is why, on the night of the 24th of October, when pro-Aoun and pro-FPM thugs attacked protesters in Mazraat Yachouh, it was a survival instinct of safeguarding the political gains they had accumulated over the past decade. For the LF and the Kataeb, participating in the demonstrations was not only an opportunity to ride the wave of the revolution, it was also an opportunity to thwart Bassil’s plan and undermine him, while on the other side of the political spectrum, the presence of Kataeb and LF partisans among protesters (even if modest) was increasingly invested to discredit the revolution in the Aounist media by unrightfully trying to portray it as an FPM vs LF-Kataeb struggle when it was crystal clear from the first day that the main slogan of the protests was “كلن يعني كلن” (roughly translated to: All politicians means all politicians are responsible).

That slogan had to be broken down by the establishment for it to be able to recycle itself into power, so on the same day the roadblock of Jal El Dib was being forced open, Mount Lebanon prosecutor Ghada Aoun gave the political class a major scapegoat for them to point fingers at, pressing charges against former prime minister Najib Miqati, 63, his son Maher and his brother Taha, as well as against Bank Audi, for illicit enrichment. One week later, State Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat would take disciplinary action against Aoun, urging security institutions not to refer cases to her anymore, due to Aoun “overstepping the prerogatives of the state prosecutor”.

Can you truly scapegoat someone if the entire class is scapegoat-able herd?

Thursday, October 24 – Day 8: The President Awakens

While Bassil had tweeted and publicly spoken for the last time on the 18th of October, and Hariri had promised and delivered his 22-item reform plan, the president had not yet given a speech or spoken to the people. So when the President finally addressed the protesters who were still forcing a strike through protests and roadblocks across the country, on the 8th day of nationwide demonstrations, the end result not only was a failure – it was a badly edited failure. For the FPM, a party that has been building its entire legitimacy on the presence of a “strong President” in Baabda palace, the idea that the president couldn’t give (too ill? too old?) a 15-line speech and that it had to be 8 days late, prerecorded, postponed for 2 hours, while being edited in a very bad way in order to hide that fact, put the FPM in a very bad position.

In his speech, the President used a very old tactic by the establishment, and asked representatives of the protesters to head to Baabda in order to negotiate their demands. That move was naive, but also smart. It was naive in the sense that it sounded like the members of the ruling parties were disconnected from reality: Never in the history of Lebanon did we see protests so decentralized, and yet the cabinet insisted that representatives head and negotiate – something that was not only unnatural in the spirit of the decentralized revolution, but also impossible to do. There was not one leader, not even thousands.

However, in his speech, Aoun’s call for a meeting was a smart way of making it look like the responsibility of figuring things out regarding the next steps and a transitional period – solely the responsibility of those in power – was now the responsibility of those revolting on the very people in power. In this osmosis, the establishment had rid itself of the burden of solving the problem and had requested from the people on the ground that they represent themselves: In that trap, it would be easier for the government and the ruling parties to decapitate a revolutionary command council by pressuring it, declaring a media war on it, and gaining leverage over some of it members, than it would be to do a systematic repression against hundreds of thousands protesting in decentralized regions across the country.

All in all, it was not ideal to shoot, prerecord and edit an old President’s speech in the middle of a revolution, and it put the government, the President, and the establishment they represent in a very weak position, galvanizing yet again protesters – who were now asking for the government’s resignation more than ever – and indirectly pushing them to stay in the streets yet again in the middle of a mid-week. Was it really that difficult to let the movement die out on its own?

Friday, October 25 – Day 9: Blame the Embassies

Since the President’s speech was an outstanding failure, Hezbollah SG Hassan Nasrallah decided to take the matter in his own hands in order to try to save the situation. As scuffles in Riad El Solh erupted between protesters and loyalists to Hezbollah who got angry when they realized that a revolution that was supposed to criticize all the political parties also included Hezbollah, Nasrallah gave a speech that was decisive in its stance regarding the revolution: He accused it of being funded by embassies, warned of a political void in case the government collapsed, saying he won’t accept any resignation of the government (basically forbidding its resignation), warned of a civil war, while also using the FPM’s same tactic of asking for the protesters to send representatives, finally calling upon the pro-Hezbollah demonstrators who had infiltrated the protest an hour earlier to leave.

The core of the speech, one must say, was rich in hypocrisy: can you really blame embassies when you’re funded by Iran? And can you really scare people from a political void when it was Hezbollah as well as the FPM who blocked the 2014 Presidential elections and kept Lebanon for more than 2 years under a caretaker government for the sole narcissistic purpose of electing Michel Aoun as President? Do you really want the decentralized protests to send representatives when you couldn’t agree as a political class on your own representatives in the government for months every time a government has to be formed? Can you really scare people from a Civil War that can happen when you’re the most armed party in the country?

However, in the establishment’s 9 day struggle to stop the ongoing wheel of the revolution, this was the first serious attempt at containing the protests. By sending its men to Riad El Solh and pulling them out within hours, Hezbollah tried to make it look among its Shiite electorate – that had been extremely active in the first days of the revolution – that the protests were destined against it, while warning – as the sole party who has so much guns – of a civil war that can degenerate from the revolution.

It was a double threat from Hezbollah, the first destined to its popular base, the other to everyone else: Nasrallah wanted to portray the revolution as a foreign conspiracy destined to bring down a government, sink Lebanon yet again in political deadlock, and threaten its stability. But in adopting that narrative, Hezbollah put itself in a very vulnerable position – it was embracing and defending the entire political class with its corruption, its dealings and its failure. Instead of simply ignoring the revolution and staying on the side (while fueling rumors that it is being supported by Hezbollah, thus discrediting the revolution in lots of regions), Nasrallah made the same strategic mistake the political class did the first 48 hours, and showed yet again the political class as a unified force in the face of a decentralized population sick of them. Except this time, he had the Lebanese Forces outside the government, so the impact of his speech was not so bad for the political class who could eventually invest it and portray the events in the country as a Hezbollah-LF (M8/M14) clash, which is exactly what started to happen – even if at a small scale – for the next few days.

Saturday, October 26 – Day 10: What Is Normalcy?

On the 26th of October, the most predictable thing in the world happened (and for all the obvious reasons in the world): Geagea decide to invest in Nasrallah’s pro-government speech by criticizing the government on Twitter. Meanwhile, and as protests were raging across the country, a big security meeting was being held in Yarzeh. It was a Saturday, and after an entire week loaded with strikes, nationwide roadblocks, and protests, the government had to prepare in advance for the second week of protests that was about to start on Monday: If they could stop the roadblocking on the very first day of the week and force things to go back to “normal” on a Monday, they would effectively kill the momentum for good and burn out the movement.

In Beirut, protesters returned to block a key bridge, “the Ring” ( Officially, the Fouad Chehab bridge) linking east and west Beirut after police had forcibly opened it in the morning. The symbolism of the ring, a major road connecting the eastern and western parts of Beirut, was crucial: What was 30 years ago the demarcation line between the Muslim and Christian parts of the city was now being blocked for exactly the opposite purpose: A symbolic unity of the city against those who used it as a fuel in their civil war feud.

Sunday, October 27 – Day 11: The Patriarch and the Human Chain

The 11th day of the popular uprising was a Sunday, and that meant two things: That the patriarch was going to talk, and that the people would be more free than usual to participate in protests. So as the Lebanese were forming a symbolic 171 Km human chain from Tyre to Tripoli, the patriach had spoken in favor of the revolution, calling on officials to listen to the people’s demands and their uprising “before it’s too late”, while also indirectly asking the protesters to unblock the roads by asking them “to facilitate the movement of people”. 4 days earlier, on the 23rd of October the Patriarch had given a much more ambiguous stance, endorsing the reforms by the government but also calling for more administrative changes, a statement that came after MP Ibrahim Kanaan of the FPM had visited the Patriarch in the morning.

Meanwhile at the ring, protesters had taken back control of the bridge after it was forced open during the morning, and in Tripoli – site of the biggest demonstrations in the country in Al-Nour square – where the army clashed in Baddawi with groups of people the day before, the protests where still going strong despite the recent events. The revolution wasn’t ending anytime soon.

Monday, October 28 – Day 12: The Lords of the Ring

And indeed, the revolution was not going anywhere. Lebanon woke up on the second Monday of the revolution to roadblocks and protests everywhere across the country. While protesters parked their cars on the highways to prevent any possible forceful opening of the roads, in the Ring, protesters who retook control of the bridge decided to furnish it instead. The government had probably put faith on the rainy end-of-the-month Monday to induce protest fatigue across the country – inspired by the sandstorm that killed the momentum of the 2015 trash crisis protests, but for some reason this time, the revolution no longer cared about the weather.

So as the government was still trying to figure out how it was going to open the roadblocks without aggravating the status quo even more, news broke out that Riad Salameh – who had been the target of several protests happening next to the central banks – had warned on CNN that the economic situation was going to collapse soon in case no solution was found soon. What was supposed to be a pro-government statement intended to convince people that they should avoid protesting in order to save their economy, the godfather of the great Ponzi scheme of the finances of Lebanon had generated more panic regarding the economic situation, indirectly fueling the protests even more, and eventually had to go on record again in the same day and clarify his comments to calm down the panic regarding the Lira.

Tuesday, October 29 – Day 13: The Sack of the Tents

So as the establishment was running out of excuses and alibis to convince the protesters to open the roadblocks and end the demonstrations on the 13th day of protests, the pro-Hezbollah minister of health took it upon himself to invest in public health in the name of the counter-revolution, announcing on Tuesday morning that pharmacies and health centers are running out of vaccines and essential medicines, spreading fake news that doctors are being prevented from getting to work and are often being asked to pay a “kickback” of between $3 to $50 to pass roadblocks, adding that local medicine factories are unable to produce the required quantities of drugs because employees are unable to get to work, and that the closure of banks had led to medicines being held at customs, with importers lacking the cash to pay duties on medical supplies. What the minister of health forgot to say is that the imminent crash of the financial sector due to the corruption and the years of mismanagement by the powers that be, would harm the patients more than any of the above: Over the last few months, dealers who bought wheat, medicine, medical equipment, and fuel in dollars and sold them in liras, were facing challenges in securing enough dollars at the official price from the banks to pay for their purchases.

As rumors started flying by noon that Hariri was on the verge of finally resigning after 13 days of protests targeting his cabinet, hundreds of organized, pro-Hezbollah and pro-Amal thugs – most certainly acting by orders of their superiors, headed to the peaceful roadblock of the ring, clashed with protesters, opened the first side of the road, before heading to the close-by Riad El Solh, Azarieh square, and Martyrs square, wreaking systematic havoc in half an hour, injuring protesters, and destroying the tents that demonstrators had set up to discuss the revolution, its goals and how to prepare for the next steps. The thuggish, unsolicited, unjustified, orchestrated, organized and planned destruction and violence on peaceful protesters – under the eyesight of a police force that enabled it and did not make a single arrest – on the 29th of October 2019 at 1PM – arrogantly in plain sunlight, by people who self-anointed themselves as judges, juries and executioners of a popular uprising, summed up the entire revolution in 1 hour. This was a fight against an oppressive regime that could not even see its opponents discussing an alternative and that was so thuggish and corrupt that it chose to resort to organized fascist violence and take the country into a civil war instead of giving up power or even staying neutral towards protesters.

And the misinformation and brainwashing by the pro-establishment media was massive. For Al-Manar – Hezbollah’s mouthpiece, what was unarguably the most violent thuggish behavior since the battles of May 2007 was considered to be a courageous act by “locals” who were removing “bandits” in order to end the crisis.

But there was only one bandit in the equation. This was a political class that closed banks, threatened with medication availability, sowed sectarian discontent, created a sham reform paper, threatened a civil war, created a false unconstitutional notion of political void, used state institutions to their own ends, and finally made use of fascist organized violence for no other reason than protect its collective institutionalized theft and illegitimate rule.

No one will ever truly know what the evil mastermind plan was. All we know is that two hours after the sack of the tents, Hariri resigned from his position as Prime-Minister.

No one will ever know what Berri and his allies were thinking when the green light was given to destroy and assault the protest sites. Was it a show of force, a message to Hariri who was about to resign? Was it an attempt to prevent him from resigning? Was it their way of showing their negotiation card in the next government? Was it a message to the protesters to stop? Was it a message to the electorate that they would resort to violence if a voice of dissent would be heard again? Was it their way of sending and spreading vibes that this was a Sunni-Shia struggle and not an establishment-revolution one? Perhaps it was all those reasons at the same time, or perhaps it was the establishment’s way of dealing with things the only way they know how to do things: Through threats, violence, and blood.

Wednesday, October 30 – Day 14: The True Conspiracy of Lebanese Politicians

For the past 13 days, Lebanon’s media outlets, high on fake news and clickbaits, have been circulating lots of conspiracy theories regarding the uprising and its “true” motives.

But the only true conspiracy was the burden that was the ruling political class. With the resignation of Hariri from the cabinet, the establishment, that has never been that weak, found an amazing opportunity to invest in sectarian discontent. Fueled by a near-total media blackout on ongoing protests , pro-Hariri protests that happened the night of the resignation throughout the country, and fake news circulating on Whatsapp – Ironically the very Whatsapp they intended to tax that started the uprising in the first place, news broke out that clashes between protesters (Some of them who were pro-Hariri supporters) and armed forces were happening throughout the Sunni areas in the country, 24 hours after the (Sunni) Prime Minister had resigned. Together with Hezbollah and Amal’s raid on the tents in Beirut one day earlier, the establishment was making it look like a Sunni-Shia clash was the reason behind the government collapse, distorting the true nature of the uprising, and using what was always known to be Lebanese politician’s last resort: Sectarianism. Through fake news, media blackout and hate, there was a quick attempt by the establishment to portray the Sunni regions – key in the downfall of Hariri through major protests in Tripoli and Saida – as regions now protesting in favor of Hariri, when it was crystal clear from the first day that the uprising was on Hariri as much as it was on anyone else. The pro-Hariri propaganda would argue that it was a conspiracy to remove Hariri, the Sunni strongman, from power, while keeping Berri and Aoun in place.

In what was probably an emotional catharsis and a survival instinct, people across the country, from the Ring intersection in Beirut to the Northern suburb of Jal El Dib, re-blocked the roads they had opened earlier that day in solidarity with Akkar. And so it was that on the night of the 14th day of the revolution, the counter-revolution finally revealed itself in full force. The counter-revolution’s plan of using the government’s collapse to split anti-government protesters into two camps had quickly fallen apart, but its true spirit remained: This would be the political class’s preferred choice of action to eventually kill off the momentum that has been miraculously ongoing for the past 14 days.

For Hariri, the resignation was a sign of weakness but was also a political investment in his future. By choosing to be the one who overthrows a government in which his party doesn’t control the majority, he manages (at least tries) to portray himself as a victim from the political class, as well as picturing himself as a “Sunni champion” who brought down the Pro-Hezbollah government despite the violence in Martyrs’ square. For Hezbollah, and the rest of their March 8 allies, the resignation of Hariri could now be portrayed as declaration of political war among their electorate: It was not your regular-day-protesters who brought it down, but a conspiracy – an act of political defiance by Hariri – to weaken Hezbollah inside the state by overthrowing their government when Nasrallah had made it clear a couple of days earlier that the government’s resignation was unacceptable.

All in all, fueling Sunni-Shia tensions by trying to make the resignation look as a conspiracy against Sunnis (for Hariri) or Shias (for Amal and Hezbollah) or Aoun (for Aounists – although Aounism is not an official religion, yet) benefited all the powers that be in Lebanon.

For Lebanon’s Muslim ruling parties, the events that happened during the afternoon of the 29th of October and the nights of the 29th and the 30th were also a political message to everyone in the country and across the political spectrum: They might have lost a government, but both were still strong enough to mobilize against each other and the revolution. In a way, it was a strengthening of the negotiation card related to their participation in the next cabinet.

Thursday, October 31 – Day 15: Sometimes Bad Things Happen

For Lebanon’s biggest Christian party, however, they had not yet given a full show of force. Gebran Bassil, infamous scapegoat of the protests, had not spoken since the 18th of October, while the President – his father-in-law – had only spoken once, making things worse with his badly edited prerecorded speech.

So on Thursday the 31st of October, on what was supposed to be the third anniversary of Aoun’s election, and as they were preparing for a massive pro-Ahed counter protest in Baabda on Sunday, the FPM started their own counter-revolution: President Michel Aoun gave his second speech related to the revolution, a speech that was supposed to resonate with the FPM defectors who had recently left the ranks of the Aounists to join with the anti-government protesters. In his speech, Aoun – standing on foot in order to squash the rumors of ill-health that went viral after his edited speech was published at the start of the protests – started by boasting his achievements during the past three years: Budgets were voted, a new electoral law was created, parliamentary elections were held, and appointments were made. After carefully explaining to the Lebanese that he actually did his job and making the Lebanese feel guilty that they aren’t being thankful enough that the bare minimum was done, Aoun proceeded to endorse many demands of the protesters, such as a government made of technocrats and the migration from a sectarian system to a civil one, while asking the protesters to help him pressure the parliament into passing reforming laws.

There were however four problems with Aoun’s speech. First, it had the traditional Bassilic trademark of sowing sectarian fears by reorienting any discussion into a refugee-themed one, as Aoun ended his talk by discussing – out of the blue – the issue of refugees and their impact, building on Nasrallah’s second speech and trying to portray the revolution as a conspiracy by foreign powers to punish Lebanese politicians who had refused that the Syrian refugees (who are Sunnis in their majority) be permanently settled in the country. Second, by asking protesters to help him pressure parliament to vote reformative bills, Aoun had admitted that he was a weak President – contrary to the entire propaganda the FPM had been trying to portray for years. Third, that request was also filled with hypocrisy: Aoun effectively had the third of the cabinet under his direct command and could also summon a majority in parliament through the network of alliances he had built throughout the years. So there was truly no need for political pressure from protesters to help him pass any laws – if his intentions were so true, especially that he was the one who refused to sign the last reformative bill that made it to the floor and sent it back into the parliament. Fourth, the president had truly not understood what the revolution was about: People wanted a clear-cut plan, and the only things that were being presented were empty promise. Even for a technocratic government, what is exactly a technocrat? And how does a promise so vague convince people to trust a technocratic minister that can also be someone from the same failing political class?

Aoun’s speech was a farce – and as protesters went back to road-blocking right after the speech (they would go on to open in the next days), it was clearly not popular with everyone. For the FPM, however it was a necessary one as they needed to build up their own momentum for the Sunday protests.

In other words, and to quote minister of interior Raya Al-Hassan’s, “sometimes, you know, bad things happen” . On the 31st of October, the (now) former minister of interior, in an interview with CNN, justified the lack of action by the police to protect protesters from Amal and Hezbollah’s thugs during the last three hours of her effective rule as interior by saying that sometimes, you know, bad things happen. If you can’t apologize or inspire accountability even after you’re removed from power, why would the Lebanese trust you? Sometimes, you know, bad things happen, and at the end of the day, Al-Hassan’s legacy at the ministry of interior will forever be linked to the last bad things that happened under her watch and her failure to protect the citizens she swore to shield from organized crime. At the end of the day, sometimes, you know, bad things happen and the failure of the political class to see that the root of the revolution was a crisis of accountability and a rupture of trust between the people and the powers that be, will be its downfall.

Friday, November 1 – Day 16: Irresponsibility, Guilt, and Paychecks

They say that guilt is a powerful tool. So when Nasrallah gave his third speech since the beginning of the revolution, guilt became the cornerstone of his political argument, after his threats of preventing government to resign failed to materialize. In his speech, Nasrallah said that “there will be no government to address the economic situations and people’s demands will be lost if the caretaking period protracts”. In his own words, Hezbollah’s SG had basically predicted the procrastination that usually comes with forming the governments by the political class, and transferred all the blame from the powers that are actually responsible of forming the next government, to the protesters who had brought down the Hariri cabinet. In Nasrallah’s very psychologically disturbing narrative, any delay in the next government would thus be the protester’s responsibility, assigning the guilt of vacancy to a revolution that had nothing to do with the transfer of powers – strictly the establishment’s responsibility.

Aside from the fact that Nasrallah’s second and third speeches had happened the day after Aoun’s first and second speech – that should give you an accurate idea on who the strongman of the political class is – Nasrallah’s stance was a clarification to Aoun’s vague words 24 hours earlier: There would not be a government without Hezbollah, and any technocratic independent government would thus be a political government that is refurbished to look as a technocratic one.

In his bid to sway Shia protesters away from the anti-government protests, Nasrallah fell into his own trap: First, he criticized “the unprecedented form and amount of cursing”, indirectly justifying the actions of the pro-Hezbollah and pro-Amal thugs who had destroyed the tents on the 29th of October and who had previously attacked protesters in the South earlier in October. The ruling class, running out of ideas, now wanted to justify its repression through “politeness”, clearly missing out on the entire idea of the revolution: This was an uprising against the status-quo, an uprising whose highlight was breaking the taboos and the constructed ideas of sanctity of the Zaim. It was a revolution in which everyone broke the fear barrier, in which protesters chanted that the speaker was a thief in his home district of the south, who cursed the foreign minister’s mom, who kept chanting against the Prime Minister until they forced him to resign, who threw bottles and spat on the leaders who tried to hijack their protests. It was a revolution based on freedom of speech and all that Nasrallah thought to do to stop it was to ask protesters to curse less.

Second, Nasrallah, in his attempt to keep the people benefiting from Hezbollah’s clientelist policies under his wing, assured to the people “that if the country fell into chaos and it couldn’t pay salaries, Hezbollah could still do”. With one single sentence, Nasrallah had destroyed the entire speech of his ally Michel Aoun, anticipating a collapse of a state the President had tried so much to emphasize its importance 24 hours earlier, and publicly taking pride in the clientelist model of his party in the middle of an anti-clientelist revolution. Out of his three miscalculated speeches, Nasrallah’s third speech was a disaster. A disaster so big that Nasrallah, who had warned the government that it couldn’t resign only a week earlier, announced that “Hezbollah was never in control of any government” while it was a general truth that the council of minister had never been so Pro-Hezbollah in years, unless Hezbollah considers Amal, the FPM and all of the rest of its partners in government rivals. Such was the power of the revolution, that it made Hezbollah abandon a government it worked 8 months to create (with two-thirds of the members direct allies of Hezbollah), fiercely defended for 14 days during the uprising, before eventually giving up any association with it, and discrediting all the influence it had with it. In less than a week, and as the banks were opening their doors for the first time in half a month and the protests where still ongoing (at a much slower pace though), the revolution had forced Lebanon’s most powerful man to renounce the King’s jewel – The 2019 Hariri cabinet.

Saturday, November 2 – Day 17: The Long Wait for the New Cabinet Begins

The second of November was a Saturday – and it was as slow as the parliamentary consultations to name the next Prime minister. It has been three full days since the government resigned, and the President had still not called upon MPs to choose the next Prime minister, with rumors around the country estimating the consultations to happen by the beginning of the following week.

Truth be told, the political class not only was in a weak position due to the decentralized protests, it was also confused by the rapidity of events, and pressured to take fast decisions it had previously taken months to come up with. In the revolution, the ruling parties found another major rival than the ones they already had among each other, and that rival was much more dangerous: It was headless – making it immune to taming, it was immense – making it immune to bribes, it was spontaneous – making it unpredictable and a threat to everything and anyone, and it was decentralized – making it immune to control by a government that only knew centralization and parties that only knew their home districts.

More than everything, the October uprising had brought a new element into the game Lebanese politicians had been masterfully playing for decades – the element of time. Known for its months-long procrastination, it was now expected from the political class (and its business partners) to designate and form a cabinet in an extremely short period of time, both to secure the financial stability – the dollar being exchanged in the black-market at 1660LBP on Friday – and to (at least try to) control popular anger. But it was a regime that invested in lengthy negotiations, and not in getting things done. When the first weekend of November came to an end without the President calling for parliamentary consultations, it was clear more than ever that the powers that be did not yet understand the purpose of the revolution: The people wanted to get things done, when the only thing the Zuamas still cared about was names and pie-sharing.

Saturday also marked a shift in the tactics of the protesters: As protesters stopped blocking roads (a method that the political class heavily criticized and used against them – ignoring that the revolution was also about civil disobedience, and resorting to a blame-shame game of protesters blocking roads), they would now start targeting the dysfunctional institutions they blamed for the crisis, also pranking politicians: While protesters made their voices heard inside the Association of Banks in Lebanon , calls for what turned to be a mock protest in front of Nabih Berri’s headquarters in Ain El Tineh generated panic as security forces as well as Pro-Amal supporters and thugs (who braced themselves for a second round after the 29th of October) rushed to secure the place from the protesters who never came. The revolution was everywhere, and it was unpredictable…even for the political genius who is Nabih Berri.

Sunday, November 3 – Day 18: Only the Counter Revolution Counts

The delayed parliamentary consultations were also a political maneuver more than anything else. Now that Hezbollah, Amal, and the FM had established their political existence in the country earlier that week, it was up to Lebanon’s most popular Christian party to establish dominance. After several days of preparations, the third of November was supposed to be the FPM’s glory day as thousands of pro-Aoun protesters gathered in Baabda. It was (1) the FPM’s own way of discrediting the revolution by showing that they too, could get large people to protest in favor of the FPM, and (2) the FPM’s way of negotiating their share in the next cabinet by correlating their parliamentary power to a popular base that they were so weak they felt compelled to prove to everyone that it still existed.

In every possible way, the FPM’s move was filled with high-quality political stupidity. By trying through their media outlets to showcase the demonstrators strictly “as LF thugs”, then by finally massively mobilizing against the anti-establishment protests, the FPM (as well as Hezbollah through its stances) had taken the LF’s bait and showcased itself as the symbol of the establishment they were the most recent to join, putting themselves first in the firing line and making it look as if the FPM were the ones who were defending the same people who used to be their bitter rivals only years ago and whose participation in the establishment dates to the 90s and is arguably more rooted and rotten (PSP, FM, Amal).

Also building on the President’s request earlier in October to lift the secrecy of the politicians’ bank accounts, FPM officials paraded the protests they organized with the announcements that they had lifted the secrecy of their bank accounts. In theory, the decision was meant to be a popular one, but in practice, there was a popular understanding by now that lifting the account secrecy was an empty decision as it didn’t cover every other possible way to launder the corrupted money that never made it into an account. The FPM had finally understood that this was a crisis of trust, but they were massively outrun by the revolution as the standards for accountability were now much higher than simply lifting the secrecy on some bank accounts.

The FPM’s maneuver was an utter failure: They mobilized on a Sunday, hoping to attract the biggest number of supporters to Baabda, only provoking literally everyone else, indirectly swelling every single other protest site in the country, where tens of thousands of people demonstrated against the establishment and its now self-made head (who brought this on himself), Michel Aoun. At every crossroad since the 17th of October, the FPM could have hijacked the revolution for their own purpose and showcased themselves as reformers who stood by the people, yet they chose to keep their political gains, when March 8 forces could have easily used the opportunity to ride the wave and form a majority government – they have both the parliament and the weapons.

Not only did the FPM put themselves in a delicate situation, but by mobilizing against the anti-government demonstrations, they also had effectively put to death any positive impact the President’s seemingly reformative plan 3 days earlier would have had on the protesters in the streets. How can you trust a president who endorsed the protesters’ demands and then mobilized against them less than 72 hours later? How can the president say out loud “I love everyone, everyone means everyone”, hijacking the anti-government protesters’ main chant and turning it against them, while also letting his son-in-law, Bassil – the infamous icon of the revolution – give a speech for the first time since the 18th of October from the Baabda Palace, when he had called for unity days earlier?

In Bassil’s totally disconnected-from-reality speech, he announces that the people had turned the table like he had previously instructed them to do, but fails to see the inevitable: The revolution had essentially turned the table on him and his government.

Monday, November 4 – Day 19: ًTeChNo-PoLiTicS

On the third Monday of the revolution, the momentum might have been high again – forcing telecom minister Choucair to change the prepaid recharge cards’ pricing from Dollars to LBP, but only one thing was higher: Walid Joumblatt’s political opportunism. The PSP leader had taken his time, bit it was now his moment to shine. As roadblocks were being set up again in the usual places, the Chouf – Joumblatt’s home district – became suddenly increasingly invested in the developments, with roadblocks being set up in some regions of the Chouf that had not seen any protesting activity before that day. It might have been possible that the setting up of some of those roadblocks has been facilitated/instructed by the PSP. After Tuesday’s sack of the tents (Amal, Hezbollah), Wednesday’s late-night events (FM), Sunday’s Baabda protest (FPM), it was now time for the PSP to prove that it still politically existed, and that it too, could control the streets.

Out of all politicians, only Joumblatt had the good political reflexes at the start of the revolution, alledgedly calling Hariri and asking for him to resign. Had Hariri, his FM ministers, the LF and the PSP resigned, they would have made it look as if March 14 forces brought down the government of the March 8 coalition with the help of the streets and protests that were heavily raging in Shiite areas too, successfully hijacking and riding the wave of the revolution, massively sending their people to help and organize in the protests and eventually using the big demonstrations of the 20th of October as a winning card. For some reason (Hezbollah pressure?), neither Hariri nor Joumblatt himself listened to Joumblatt and they did not invest in the LF resigning from the cabinet on the night of the second day of the uprising, missing out on a crucial political opportunity. Once again, the political class – clever masterminds of their own continued presence in power since 1990 – had surprisingly missed out on every crucial crossroad to kill the revolution: Power eventually makes you blind.

Meanwhile behind closed doors, Hariri and Bassil had a 4-hours meeting on Monday, in which – one would assume – they discussed the name of the next Prime Minister as well as the details of the next government formation. Anti-establishment protesters on the ground had made it clear they wanted a government made of “technocrats” unrelated to the political class, but the counter-revolution that began on the 29th of October made it clear that the powers that be were not going to leave the executive power, and a new concept was being floated in the weird world of Lebanese politics: A government that would be a mix between technocrats and politicians so that ruling parties would keep an eyesight on the ongoing businesses, orchestrating their slow inevitable comeback into the Lebanese council of ministers. The Lebanese media, who gets high on terminology, started calling it “techno-politics”. There was no DJ to entertain Hariri and Bassil, but they were most certainly entertaining the entire country with speculations of techno-politics being cooked up. And as if Lebanese politicians needed one more thing to increase pressure on them, news broke out that the U.S. were freezing military aid to Lebanon.

Tuesday, November 5 – Day 20: Shifting Tactics

24 hours later after the protests in the Chouf had suddenly increased in intensity and frequency, Walid Joumblatt quickly did quality control to avoid the protests eventually going out of control and backfiring against him, tweeting that some things in the Chouf were red lines for protesters, such as a statue in Baakline. Joumblatt had to quickly contain the protests, and in his use of a Civil War memorial building, found a smart way to calm the tensions that he might had instigated a day earlier for political gains.

Elsewhere north, the roadblocks of Jal El Dib and some roadblocks northern Mount-Lebanon – heavily invested by the LF and Kataeb – were once again set up by protesters. The LF and the Kataeb were probably sending the same message Joumblatt was, and in the exact same way (talk about the creativity of Lebanese politicians). It was a proof of existence from the LF and the Kataeb to be used as a negotiation card for the next cabinet. The speed and relative swiftness in which those roadblocks across the country were opened later that day by the army could also be a hint of political use of the revolution’s methods for the counter-revolution to do its own bidding. It was also a sign that the establishment had finally adapted to the revolution’s tactic of closing roads – even using the decentralization and leaderless-ness of the revolution in order to endorse it for its own ends.

So as the counter-revolution finally adapted, the unpredictable revolution changed its tactics.

Always remember, remember, the 5th of November, the day protesters gave up on the roadblocks (that the pro-establishment media had been criticizing in their media war), and eventually re-oriented the demonstrations into decentralized precision moves destined to cripple the country’s universities as well as dysfunctional or corrupt institutions, closing or protesting in front of Banks, Banque du Liban, Electricite du Liban, telecom companies, among other state owned facilities throughout the country. In the pro-media outlets, journalists sympathizing with the revolution started resigning en masse.

Meanwhile among the ruling political class, a new tactic was being implemented. The powers that be were playing the time card, as Aoun still hadn’t called for parliamentary consultations even one full week after Hariri had resigned. Calling for the consultations without having already figured out every single detail related to the cabinet would mean that the ruling parties will have to bicker and jockey among themselves in public, weakening each other as well as their collective position regarding the protesters, the last thing they would want at this moment, whereas agreeing to everything among themselves behind closed doors made much more sense now that every single one of the ruling parties had made its own strength parade.

The problem with the behind-the-scenes pre-consultations decisions is that they effectively stripped the next Prime-Minister designate of his authorities to choose (or at least have the illusion of choosing) his own government, unofficially distributing it on the Zuamas of the country, who were now negotiating among themselves on an entire package once and for all (Prime Minister, ministers, ministerial declaration, next steps), instead of doing things – like the constitution advises you to do – one step at a time. But for the counter-revolution, there was no time for the constitution: They could no longer afford to publicly bicker among themselves – Even though Claudine Aoun, the daughter of the President and wife of a Aounist MP and former general Shamel Roukoz, publicly criticized Gebran Bassil, her sister’s husband, for his show of force on Sunday. All in all, it was a nice show of inter-nepotist fighting for the revolution to enjoy, especially after Roukoz and Neemat Frem had resigned and (theoretically) defected from the FPM’s bloc during the first days of the uprising.

As Moody was downgrading Lebanon’s rating to Caa2, news broke out that the financial prosecutor Ali Ibrahim was suing the CDR as well as several firms and an ex-minister for negligence and corruption. The political class needed to buy time, and there was no better way to calm the streets than to send a message that the judicial authorities are becoming functional again.

Wednesday, November 6 – Day 21: Are They Really Binding Consultations If They Do Not Exist?

In the true correct universe of Lebanese politics, the plan of the political class to form the next government (or at least to choose the next Prime Minister) outside the framework of the constitution (Before calling for parliamentary consultations) could have caused sectarian tensions as it would have been politically used by Sunni figures to portray it as a violation of the Sunni Prime Minister’s authority of forming the government. But the correct universe of Lebanese politics had died on the 17th of October, and this was a entirely different playground, so the establishment did not eventually really care about the mechanics as much as it wanted to let the protests die out on their own without triggering another revolution with a controversial government formation. So instead of playing the usual cat-and-mouse game regarding the authorities of the Prime-Minister designate, Saad Hariri was reportedly quoted saying that the unofficial consultations were only regarding the name of the next Prime Minister, did not include the formation, and were not an assault on the authorities of the PM designate to form the cabinet. Even in his modest attempt to reestablish a little bit of the political dominance he lost within his Sunni electorate, Hariri fell into his own trap of sectarianism, spreading rumors that the off-label behind the scenes discussions that have now been happening FOR 9 DAYS were only about the name of the next Prime-Minister, and not even about the formation of the next cabinet. Do you really want to convince the people who overthrew you for incompetence that the sole choice of the name of the next Prime Minister did not yet materialize in 9 days? How politically naive can the establishment be?

How politically naive can the establishment be to plead for the unconstitutional ways of forming a government outside a constitutional platform, before eventually hinting at the inefficacy of the method, in the middle of a financial crisis and a revolution fueled by anger over governmental incompetence?

Truth be told, the revolution had changed its ways, but it was yet to lose momentum despite the stalling in government. On the 6th of November, and as part of a response to a provocative decision by a school official – a pro-Aoun nun – to punish pro-revolution school students, thousands of students across the country protested in schools and universities. For some reason, the establishment was still not convinced that letting the protests die out on their own in the cold rain of November was an option – they somehow had to be provocative in every single possible way. By the 6th of November, the only conspiracy keeping the revolution as active was its same trigger: The arrogance, political incompetence of the ruling class and its partners across the country.

Meanwhile elsewhere in the country, and while the counter-revolution was figuring out innovative ways of opening roads, this time through a lawsuit from FPM lawyers calling on the public prosecutor to take appropriate action against protesters for “infringement of freely moving across the country … and causing material and moral damage to citizens”, the uprising had completed its tactical shift from roadblocks and barricades to an increased targeting of state (judicial, telecom, public) institutions as well as illegally built resorts. Pot-banging on balconies and in demonstrations also became a way of protesting – through noise and a collective public action – against the status quo and the powers that be.

Thursday, November 7 – Day 22: Amnesty and Scapegoats

On the 22nd of the uprising, the establishment spread the news that a parliamentary session scheduled 1 week later, on Tuesday the 12th of November, was intended to vote four “reform” laws on its agenda: A draft law on fighting corruption, a law establishing a court for financial crimes, a law to create an elderly pension system, and a law for a general amnesty (intended for petty and drug and non-violent crimes) . The parliamentary session was also unconstitutional as it was programmed to happen with no cabinet in power, during a period in which parliament was supposed to legislate a budget before anything else. The political class, in its quest to calm down the ongoing protests, made it look like they were making an effort to give the people anti-corruption and “quality-of-life” measures. In practice, however, the draft laws to be passed on Tuesday would only ameliorate the quality-of-life of politicians: The draft law on fighting corruption is not as practical as the politicians would want you to think, the court for financial crimes would be appointed by the politicians in parliament and government- beating its purpose, and the law for a general amnesty would include a lot of potential crimes related to the finances and to the corruption of the ruling class, while it was yet unclear how the parliament could pull an elderly pension system when the country is on the verge of bankruptcy. The establishment had finally started to build on empty promises, but the promises they intended to deliver were outright bad and were intended to shield them from accountability through amnesty.

Indeed, this was an uprising about accountability, and all the politicians were thinking about was how to pass a general amnesty and create sham judicial authorities and mechanics to pursue them. And the protesters didn’t quite fall for the trap of empty and bad promises: Thousands of school and university students across the country marked the 22nd day of nationwide protests on Thursday morning, marching through the streets and gathering in front of state institutions. The revolution had reached the schools on the 21st and 22nd days, as students went to the streets and protested inside and outside their schools and universities. For the past three weeks, the opening of schools and universities had been a key question in Lebanese politics because it was one of the major determinants of normalcy. If educational institutions can run smoothly, it would be a clear determinant of normalcy, a normalcy that the ruling parties had been craving to come back to for more than three weeks.

When in mid-October, on the first week of the uprising, minister of education Chehayeb asked schools and universities to open (before rapidly backtracking his decision in the same day after it backfired), it was a clear attempt from the establishment to indirectly push the roadblocks to ease by forcing anyone and everyone to go back to the daily routine. So when the schools and universities gradually and finally opened during the third week, the decision from the students who were involved in the uprising to disrupt the functioning of the educational institutions and to bring the revolution with them to classes and outside classes was a spontaneous act that became a major blow to the establishment: The revolution was viral, and the momentum was still high enough (though not as high as the first 10 days) to put enough pressure on the state’s institutions.

And the pressure was high, not only because of the students’ movement. For the past few days, investigative journalists such as Riad Kobaissi of AlJadeed had been leaking and discussing several corruption scandals, putting the Lebanese judicial authorities under immense pressure, and pushing financial prosecutor Ali Ibrahim to order former Prime Minister Fouad Siniora to appear for questioning over some $11 billion spent during his term as premier ( a time when the state did not pass budgets), as well as pressing charges against the head of the Flight Safety Department at the Directorate-General of Civil Aviation. Ibrahim – who eventually listened to Siniora’s testimony after the latter had initially refused to meet him – also brought on the 7th of November charges of squandering public money against the infamous pro-FPM Lebanese Customs head Badri Daher. By giving up scapegoats for the sake of ignoring collective corruption, the political class had effectively started to eat each other up, and had indirectly only given a positive reinforcement for the uprising to continue.

In practice however, all the establishment was doing was an attempt to buy time and cover up their ongoing procrastination regarding the next cabinet. Bassil and Hariri had met for the second time this week one day earlier, and it started circulating in the media that the political class was yet to agree on the next steps regarding the new council of ministers. So on the 7th of November, when Hariri met Aoun in Baabda, rumors that have been flying for some time intensified in quantity: It was being circulated that Hariri only accepted to come back as head of a purely technocratic government, while the pro-March 8 politicians wanted him to come back as head of a techno-political government. A new deadlock was taking shape, and the confusion between the different Lebanese politicians could be seen by the fact that they were still discussing the next government behind the scenes and outside constitutional frameworks: The President was yet to call for parliamentary consultations

Friday, November 8 – Day 23: The Great Contradiction

Because the pressure from the streets was too mainstream, the Lebanese political class had to deal with multiple new problems on Friday: As protesters kept their paralysis of state institutions (through protests in front of Electricite du Liban, the education ministry, the port, the justice palaces, among other institutions), hospitals warned that they were going on strike in 7 days (due to the state’s nonpayment), the Lebanese Syndicate of Gas Stations Owners had announced on Thursday that gas stations are about to run out of gasoline very soon due to the U.S. dollar crisis, and last but not least, Civil Defense warned of wildfires – one of the major direct triggers of the revolution – as temperatures rise again 10 degrees more than the yearly average.

The counter-revolution, in its attempt to ethically demoralize the participation of students in protests, decided that the best way to do so was to spread fake news through the National News Agency, claiming that international organizations have warned Lebanon after noticing kids aged 18 and less were taking part in the protests. Remember when the head of the NNA was removed and replaced by a pro-Bassil figure during the first week of protests? Now you know why it happened.

Even with all the pressure by the protests and the country’s institutions, the President still hadn’t called for parliamentary consultations, making it clear that there was a clear problem for the political class. Ironically enough, the March 8 parties insisted that Hariri comes back as Prime Minister, and for several reasons:

(1) The presence of Hariri at the head of the cabinet would justify the presence of high-ranking March 8 politicians in government (such as Bassil and Hassan Khalil), effectively turning any cabinet into techno-political one and not a purely technocratic cabinet, serving the purposes of the March 8 alliances who would see their absence in the next cabinet as a blow to their influence especially that they had won the 2018 parliamentary elections. Thus, the best case for the March 8 parties to form and justify a political cabinet in which they could still exert influence would be by bringing someone who is an unquestionable March 14 figure, bringing more legitimacy to the new cabinet in the progress, and avoiding targeted backlash from protesters and pro-March 14 figures against them if the government has controversial ministers among its members. Ironically, the only way for the FPM to save their Ahed was by bringing back Hariri into the cabinet.

(2) The presence of Hariri at the head of the cabinet would also make it possible for the March 8 parties to scapegoat him in case something (or anything) goes wrong, as it is usually the executive power in Lebanon, and most importantly its head – that takes the blame and is usually accountable for the actions of the entire political class: Between the 2010 and 2019, Lebanon only had 1 parliamentary election while the Prime Ministers resigned or were ousted 4 times. By putting a pro-March 14 figure as head of a March 8 cabinet, March 8 parties get to do as they please while throwing all the blame on another camp in case things go bad – the prime example being Nasrallah denying that the 2019 Hariri cabinet was Hezbollah’s cabinet after Hariri’s resignation on the 31st of October, while his previous speech a week earlier was an outright defense of the government (for the simple reason that it was dominated by Hezbollah’s government).

(3) A political cabinet without Hariri and March 14 parties means that Hezbollah, Amal and the FPM would have to form a one-sided March 8 political (or techno-political) cabinet – since there is a refusal to form a purely technocratic council of ministers by Hezbollah – which would: (a) Anger the initial protesters, (b) anger every other human who still supports the March 14 parties, (c) attract sanctions from the international community while jeopardizing the economy even more under their direct rule (especially that Pompeo had asked Lebanon to dismantle a Hezbollah missile factory on the 6th of November), threatening the availability of the CEDRE funds and thus the worsening of the economic situation, also (d) forcing Hezbollah, the FPM and Amal to assume the responsibilities of anything that can go wrong, economically and financially. It would be pure political insanity for the FPM to include Bassil in a cabinet in which Hariri was not even present. Hezbollah, through the words of Naim Kassem, also insisted on being represented, and the easiest way to justify the presence of Hezbollah ministers would be by choosing Hariri to be Prime Minister

By resigning, Hariri – who had showcased himself as a weak Prime Minister over and over again – had effectively liberated himself from his partners in the previous government while increasing his leverage in power. For all the reasons cited above, Hariri’s alleged insistence on coming back only if he is the head of an independent government of technocrats and not the head of a political or techno-political government is his way of extracting a political victory from his rivals out of what was previously a major defeat (his resignation). In a way, Hariri also needed to come back as Prime Minister for him to save his legacy: His three previous cabinets have been disasters, and if he manages – somehow, somehow – to get Lebanon out of the financial pit it is drowning in, it would save his political career.

Saturday, November 9 – Day 24: The Damned Dam of Bisri

On Saturday, less than 24 hours after the Civil Defense had warned that Lebanon was at great risk for wildfires for the next few days, a wildfire in Debbieh (Chouf) brought bad memories of the huge wildfires that ravaged the country in mid-October. The revolution was also about accountability for the major environmental mismanagement in the country from the electricity and water sector, to systematic deforestation, to trash collection, to the bad dam policies.