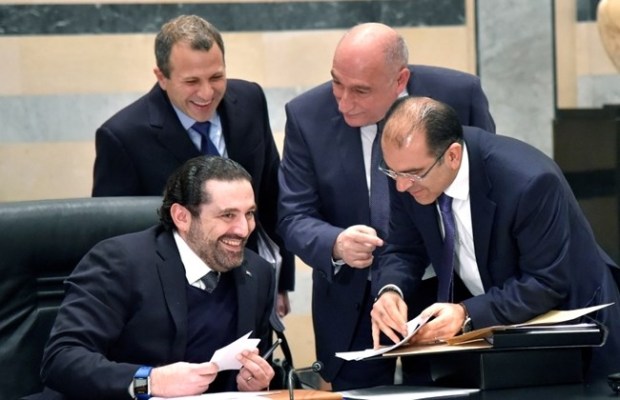

PM Saad Hariri with Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil and two other government officials at the Grand Serail. Friday, February 17, 2017. (Image source: The Daily Star). As Lebanese parties start their drama ahead of next year’s planned elections, this picture is here to remind you of the hypocrisy of Lebanese politics.

On the 4th of November 2017, one year after he was named Prime Minister (on the 3rd of November 2016), and in what might be the most unpredictable political stance of 2017, Prime Minister Saad Hariri unexpectedly resigned from his post of Prime Minister, citing Iranian interference, Hezbollah’s arms, and fear of assassination as motives for his resignation, and opening a new chapter in Lebanese politics.

An unpredictable and unexpected resignation

Until the last days of October 2017, things seemed to work out relatively smoothly between the anti and pro-Syrian regime parties of the Lebanese ruling coalition, with the appointment of a Lebanese ambassador in Damascus being the latest example of political events that could have blown up the coalition but didn’t. Other examples include state budget talks, voting an electoral law, passing a new tax law, and a new oil tax law. True, there were numerous confrontations between the ruling parties in 2017, but for the first time since at least 2010, there was peace and love in Lebanese politics. Who would have thought in 2009 that Hariri would name Aoun as his presidential candidate in 2016? That Aoun would afterwards name Hariri prime minister? That a government could be formed so fast in Lebanon? That they could agree on the garbage file or any other file? That an electoral law could ever be agreed upon by almost all of the ruling parties?

The idea that Amal, Hezbollah, the Future Movement, the FPM, the LF and the PSP could happily coexist together in a government led by Hariri in a Aoun Presidency seemed so surreal that everyone got adapted so quickly to it, and Hariri’s resignation will come as a shock for many Lebanese who got used to the climate of political cooperation between the anti and pro-Syrian regime parties that had been flourishing since last autumn.

Actually, not that unpredictable and unexpected

There remained however a major obstacle that couldn’t let that unconditional love (note: Read “unconditional love” with sarcasm) thrive in Lebanese politics: Lebanon’s parliament recently voted an electoral law based on proportional representation, which meant that it was now impossible for the Lebanese ruling parties to run together on the same ticket because such a scenario would open the door for third-option parties to thrive on the absurdity of such an alliance, and threaten the status-quo just like what happened in the 2016 Beirut municipal elections – except that this time the newcomers would be able to actually win seats because of the new proportional electoral system. It’s wiser for the traditional political parties to run against each other than to run together against a third option. As an example, it makes more sense for the Aounist electorate to vote against Hariri and for the FM electorate to vote against Aoun, and it would be easier for all the traditional parties to win back their electorates by creating sectarian tensions against one another than it is to win elections by proving that their cozy comfy alliance with a previous Civil War rival is healthy (also read this with sarcasm) and that they aren’t corrupt.

In the Lebanese political context, hate is more efficient when it comes to winning votes. Hariri’s resignation, including his violent anti-Iran quote in his resignation speech (“Our nation will rise as it did in the past and it will cut off the hands that are reaching for it”) was an essential requirement for him to distance himself from Hezbollah – with whom the Future Movement has been sharing power SINCE 2014 – and re-establish the two camps that shaped 2009 pre-electoral Lebanon: The March 8 and March 14 coalitions.

The Mikati-Rifi prophecy?

The only thing more predictable than Lebanese politicians is Lebanese politicians, and even in their unexpected Jumblatt-like stances, like Hariri’s recent resignation, Lebanese politicians do the same polititcal maneuvers when they are forced into similar circumstances. Hariri’s violent breakup with Hezbollah was thus likely to happen anytime before the end of 2017: In my last post on this blog, in August, I had said that with the objectives of the ruling parties completed in parliament […] one should expect an environment of political escalation between Hezbollah and the FM as they progressively start to brace themselves for elections.

In fact, the unpredictable nature of Hariri’s resignation was part of a very predictable maneuvering pattern in Lebanese politics. On the 4th of November 2017, 13 years and 2 weeks after his father resigned from the Prime-Minister post ahead of scheduled elections, Saad Hariri did the exact same thing. But the Hariris are not the exception. In fact, they tend to be the rule: On the 22nd of March 2013, Najib Mikati resigned from the premiership of a Hezbollah-led cabinet, 2 months ahead of scheduled elections. Less than three years later, on the 22nd of February 2016, two months before scheduled municipal elections, Ashraf Rifi also resigned from the Justice ministry of another cabinet in which Hezbollah was participating.

In a way, 2013 Najib Mikati and 2016 Ashraf Rifi had warned us that a day like the 4th of November 2017 would eventually happen: It is unwise for a Sunni politician to run for elections while being allied to Hezbollah. And for a politician who elected Hezbollah’s candidate as President, running for elections as a sitting Prime-Minister of a Pro-Hezbollah President after sharing power with Hezbollah for almost 4 years, is even more unwise. The timing of Hariri’s *unexpected* resignation is perfect: It gives an impression that Hariri is not a pawn of Aoun or Hezbollah (since he didn’t apparently consult with any of his partner in power before proceeding with his resignation), and sends an other interesting message. In fact, Hariri’s resignation from being Aoun’s Prime Minister happened outside Lebanon, in Saudi Arabia, and is technically very similar in terms of humiliation to what the FPM and Hezbollah did to Hariri when they brought his government down while he was meeting Obama in the United-States in 2010 (Hariri has probably waited for this moment for 7 years). It is usually preferable that the PM resigns from Baabda palace, and Hariri’s method of resignation, far away in Saudi-Arabia, is a message to both the FPM and Hezbollah: Aoun knew of the government resignation by phone. Revenge is a dish best served cold. Or via a phone call.

The resignation also creates many problems for Hariri’s Sunni rivals: Should the new designated Prime Minister come from outside the Future Movement or without its blessing, he will be definitely seen as Hezbollah’s puppet before elections. In a way, Hariri’s timing and place of resignation made it quite impossible for any of his major rivals to thrive instead of him in the premiership or make use of their new Prime Minister post for the upcoming elections, and the Prime Minister job opening at the Grand Serail will be a trap for any Sunni politician with an ambition to topple Hariri in the future. Just ask the Karamis of Tripoli.

The first consequence of the 2017 Adwan electoral law

One of the worst aspects of the new electoral law that was designed by Bassil and Adwan started to unravel: While the electoral law was based on proportional representation for the first time in the history of Lebanese parliamentary elections, it implemented a weird Kadaa-based preferential voting system that made it easier for sectarian parties to pick up MPs from their sect (so that the FPM and LF manage to win the Christian seats), which would potentially lead to even more sectarian-based political campaigning. A Hezbollah-FM electoral alliance would thus not be as efficient for those parties, and the two rivals would benefit the most from the new electoral system and would pick up same-sect seats the most if they run against each other instead of running on the same-ticket. The new electoral law doesn’t make it easy for cross-sectarian alliances to thrive, so Sunni-dominated-FM and Shia-dominated Hezbollah had no electoral reason to keep their alliance alive and run on the same ticket (like they did in 2005) .

In a way, it also helps explains why Hariri weirdly resigned from Saudi-Arabia: He could have resigned from the Grand Serail in Beirut, but he wanted to send an exclusive message to Lebanon’s Sunni population that he was the Kingdom’s chosen Lebanese politician, and that not voting for him in the next elections would be a vote for Iran. The Adwan-Bassil new electoral law gave a possibility for politicians to win seats from the same sect in a proportional system, and the resignation in Saudi-Arabia was a bold move from Hariri, with one goal: Turn the sectarianism button on, and rally as much as possible of the Sunni electorate in order to get the most possible religiously homogenous parliamentary bloc in 2018.

A magnet for the LF?

Most of the events months of September and October 2017 went unnoticed in Lebanese politics, with the regular bickering between Lebanese politicians progressively escalating, inspired by the approaching elections. There were however several stances and political developments that set Hariri on this path: On the 9th of September, the deputy-PM and the LF’s highest ranking politician in the executive power said that Hezbollah infringes on Lebanon’s sovereignty, on the 13th of September Geagea was criticizing Iran, on the 16th of October, Geagea said that the return of Assad’s influence to Lebanon was a red line, and by the 23rd of October, Geagea was threatening a resignation of the Lebanese Forces ministers from the cabinet. Geagea and Gemayel had travelled to Saudi Arabia at the end of September, and while the LF and the FM were taking major anti-Hezbollah position in the government, new tensions started appearing when Berri took advantage of a chaotic context regarding the preparations for the elections, and said that the parliamentary polls should be brought forward if the magnetic card wouldn’t be used, which kind of stressed out everyone even more, eventually proposing a draft law to slash the parliament’s extended term. The debate on the mechanism of the next elections continued for two months, creating tensions between the FPM and the FM, with interior minister Machnouk arguing that “the pre-registration of voters has become inevitable,” while seeing an “inability” to create voter cards—as per Bassil’s insistence– due to lack of time.

Regional influence and local politics

In his last cabinet meeting, a couple of hours before he resigned in Saudi Arabia, Hariri had reportedly told his cabinet that Saudi Arabia was “keen on Lebanon’s stability”, despite the fact that it was previously reported this week that Hariri was asked by Saudi-Arabia to distance himself from Aoun, and that it was also previously rumored in the mainstream media that the same things were asked of Geagea and Gemayel who visited the Kingdom in September. Saudi Arabia’s role in the resignation is crystal clear, and Hezbollah will probably use Hariri’s place of resignation against him (in electoral campaigning) till the end of time.

Several developments probably led to the resignation. The FPM-FM (Bassil-Machnouk) heavy political clash on the electoral mechanism of voting may have played a part in the collapse of 2016 Lebanese coalition , Saudi-Arabia’s rising influence and Hariri’s recent visit to Saudi Arabia where he met a Saudi minister who had taken a hobby of publicly criticizing Hezbollah might have given Hariri the Saudi-Arabaian green light (reminder that Hariri also resigned from Saudi-Arabia), but Geagea distancing himself from Hezbollah (inspired by the talks he did in Saudi-Arabia at the end of September?) should be seen as the main culprit in the collapse of the LF-FPM-FM-Hezbollah alliance. Hariri, via the timing of this resignation, was also probably trying to attract the LF away from the FPM by building on the Lebanese Forces tensions with Hezbollah in the cabinet. The LF are at a stage where they should choose between an electoral alliance between the FPM or the FM, and the FM exiting the Hezbollah-FPM-FM-LF coalition (via Hariri’s resignation) at a time when Geagea was criticizing Hezbollah, could push the LF away from an electoral alliance with the FPM. It was Hariri who pushed Geagea towards Aoun in the first place when he endorsed Frangieh as his presidential candidate in 2015, and now an opportunity to bring Geagea back into the fold of a March 14 alliance had presented itself. Another key political development that played a part in the resignation was the reconciliation between Hariri and Jumblatt on the 9th of October, followed by the PSP’s criticism of Syrian regime via Marwan Hamadeh at the end of October.

With an alliance with the LF and the PSP now possible, Hariri’s abrupt resignation was possibly the first step towards achieving his ultimate goal of reforming the 2009 March 14 alliance ahead of the 2017 elections. It remains to be seen how Geagea and Jumblatt would eventually react to the resignation and time will tell if Hariri’s maneuver will work, especially that the electoral law has changed, but it was nevertheless the best timing for Hariri to proceed with his move, a move that was necessary if he wanted to truly challenge in the next parliamentary elections while being seen by the Sunni electorate as a leader of a coalition that rebelled against the status-quo rather than a puppet Prime-Minister who had allied himself with the parties he initially ran against in the 2009 elections.

The republic of chaos-control

Four days prior to Hariri’s resignation, Aoun was celebrating the achievements of his first year in power, while not long ago, Hariri was also doing the same. When elections come, there will be a struggle between the FM and the FPM to define who was the main man behind the success, and who was the culprit behind the shortcomings of the cabinet. A particular example of shortcomings was during July and August when the Lebanese ruling parties allowed and banned rival protests regarding Syrian refugees, started a war in the Arsal and Ras Baalbak outskirts, and eventually set free hundreds of ISIS terrorists, while using all those distractions to pass a new tax law that was eventually deemed unconstitutional.

When they fail, Lebanese politicians change the political debate at a speed that makes it difficult for anyone to keep up with, while making sure they remain at the epicentre of any new political debate. This method of chaos control is frequently used by the traditional parties and the new political developments in Lebanon turned the Summer of 2017 into a distant past for everyone involved, while Hariri’s resignation from premiership at a time when the government was the least efficient leaves the responsibility of the fiasco of the Summer of 2017 resting solely on the shoulders of the FPM (via Aoun), although it is too soon to see how the Lebanese parties plan on campaigning before elections.

Another parliamentary extension?

Governmental resignations are not very promising when it comes to holding elections on time, and the last time a government resigned before elections in 2013, we ended up with 3 parliamentary extensions (it took 11 months for the government to be formed and the elections were due to be held in 2 months). Lebanese politicians now have the perfect opportunity to procrastinate regarding the formation of a new government that would oversee elections, and their true resolve on holding parliamentary elections on time will be tested soon enough. The sooner a new government is formed the more likely elections will happen.

The FM and the FPM knew exactly what they had to expect in government when they decided to go forth with their alliance in 2016, and the entire drama that will unravel in the next few weeks only has one goal: Electoral campaigning, and the reconstitution of the March 8 and 14 alliances that were shattered by the Presidential elections.

In other words, expect a lot of “Hariri is a Saudi puppet who resigned in Saudi-Arabia” vs “Iran wants to control Lebanon and we will not accept its meddling” in the coming weeks, and welcome back to 2008, Lebanon. It’s been a while.

This was the 31st post in a series of bimonthly / monthly posts covering developments in Lebanese politics since June 2014. This post is about the months of September and October 2017.

One comment

Comments are closed.