Disclaimer: All the numbers used in the proposal are based on Lebanon’s 2013 electoral lists that I took from the awesome lebanonelectiondata.org website. The numbers could be a bit inaccurate (the government sometimes forgets to remove deceased electoral voters), but it’s the only thing I could have worked on right now.

Lebanon’s quest to find a fair electoral law has so far been a failure. Throughout the 1940s and the 1950s, the different Lebanese governments were accused of holding elections under gerrymandered laws that kept them in power. Parliamentary elections were known to be rigged in order to safeguard Bechara El-Khoury’s regime and promote Khoury’s reelection. Khoury eventually left power, but in 1957, a new electoral law resulted in the defeat of several of the opposition’s leaders throughout the republic, and the accusations of gerrymandering as well as the calls for a fair electoral law were among the main elements that led to the 1958 uprising. Another law was consensually adopted in 1960, but will go down in history as one of the indirect causes of the 1975 civil war. After the war, several electoral laws (1992, 1996, 2000) were adopted but their primary role was to keep a pro-Syrian majority in parliament. Lebanon eventually re-adopted a modified version of the 1960 electoral law in 2008, but it was considered to be outdated and unfair by many. Several attempts to find another consensual law failed, and the Lebanese political class, refusing to head to elections under the 2008 law while unable to find a fair or even consensual alternative, has successfully extended the current parliament term twice, in May 2013 and in November 2014. Beirut has recently been busy with anti-government protests, and as citizens take the streets and ask for reform, solutions for the trash crisis and early elections, the electoral law debate would eventually complicate any call for early elections.

Lebanon needs a fair electoral law now more than ever. This is why in this post, I’m going to talk about an electoral proposal that has not yet been mentioned nor discussed. The concept of the law is based on fairness, equal representation for all Lebanese citizens, equal representation for all regions, historical constituencies, safeguarding the current sectarian representation, and most importantly, a system automatically moving seats before every parliamentary election in order to stay updated and proportional to the number of registered voters in every constituency. I’m going to get into the detail of every aspect of this electoral proposal and try to explain it as much as possible.

- The General System: Proportionality

The main criticism of Lebanon’s previous electoral laws is that they weren’t representative. The current law (and many of the ones before it) adopted a majority system. This means that if a list of MPs got 35% of the votes while the two other lists got 32.5% each, the coalition that didn’t even get an absolute majority and that only got a 2.5% advantage over its rivals would get all the seats. To make things worse, some of the constituencies had/have a high number of seats (like Baalbak-Hermel with 10 seats under the 2008 law and Beirut with 19 seats under the 2000 law) and thus had a representation in parliament that wasn’t accurate at all. Since most Lebanese MPs now run in lists, the unfairness of the representation is often found in most of Lebanon. The proportional system solves this issue by allocating a number of seats for every list proportionally to the number of votes it got. Take Beirut III in 2009 for example. The March 14 coalition got around 79% of the votes but still managed to take all 10 seats. If the elections were held under proportional representation, they would have gotten 8 seats and left 2 for the March 8 alliance. The same could be said in the district of Keserwan, where the March 14 alliance got 44% of the votes yet ended up with 0 MPs out of 5. If the elections were held under proportional representation, they would have gotten 2 seats. That unfairness is found in most of the constituencies, and a much better representation could be achieved with proportional representation.

There’s another electoral proposal in Lebanon, known as the Fouad Boutros law in which you have small districts (the cazas) with majority representation (71 seats) and bigger ones (the muhafazas, that include the cazas) with proportional representation (57 seats). The problem with such mixed laws is that they could be misrepresentative towards the regions: A caza with an originally low number of seats (like Bcharre) could not give any seat to the muhafaza (like the North, for Bcharre) while another one with a bigger number of seats (Akkar, for example) could see many of its seats transferred to the muhafaza, which would mean in the end that Bcharre, already overrepresented, will be even more overrepresented while the opposite would apply for Akkar. That was the case with mixed law proposals the Lebanese forces party or even March 14 introduced in 2013. But it’s not only about being unfair to the regions: There is no clear/simple mechanism of how the seats would be allocated, and their distribution would hence be restricted to the government. In other words, political parties could move seats as they wish before every elections in order to control the results as much as possible, which would severely harm the democratic process. If the system was only based on proportional representation, there is a way, via a formula – explained afterwards – to divide the seats automatically without interference from political parties. Another problem with the mixed law is the ethical debate that would eventually come with it: Who is more legitimate in the Lebanese parliament, the member of the parliament that is elected by the caza under a majority system, or the member of the parliament that is elected by the muhafaza under a proportional representation system? The Constitution (via Article 27: A member of the Chamber shall represent the whole nation. No restriction or condition may be imposed upon his mandate by his electors) stipulates that every MP in parliament represents all the Lebanese people, which eventually means that all MPs are equal in their representation. But will it really be like that in parliament?

- Five Districts, The Historical Regions of Lebanon: No Gerrymandering and Better Representation

Now that we’ve established that proportional representation would provide the fairest representation for any multiple-seats constituency, the remaining dilemma would concern the size of the constituencies (in terms of number of MPs), and their geographical borders. Now this is the part where most of the political gerrymandering is made, which is why, and in the simplest way to avoid that, the best choice for an electoral map of Lebanon would be to choose the five historical regions as constituencies: the muhafaza of Beirut, the muhafaza of Mount-Lebanon, the Greater North (the muhafaza of the North and the muhafaza of Akkar), the Greater Bekaa (the muhafaza of the Bekaa and the muhafaza of Baalbak-Hermel) and the Greater South (the muhafaza of the South and the muhafaza of Nabatieh). One could easily say that the constituencies are too large, and that they are more or less similar to the ones that were established under the Syrian tutelage. But then again, there wasn’t proportional representation in the Syrian era, and it was the winner-takes-all system that made the results unfair. In fact for a proportional representation system, the bigger the constituency is (in term of voters), the more the results become accurate. For example, if a party gets 30% of the votes in three districts, each with 4 seats each, it will end up with 3 MPs (1.2 MP => 1 MP per district). But if the three districts are joined together, it becomes more representative and the party will get 30% of 12 MPs = 4 MPs.

So why not make Lebanon as one district (like the Israeli electoral system)? Because some entire regions might become underrepresented and others overrepresented: A simple example is that none of the Lebanese political parties has a leader or even high ranking officials hailing from the Bekaa, which would mean that the têtes de listes would be in their majority from other regions, and the Bekaa, that deserves around 21 MPs, might end up with 10. By keeping every historical region alone, one avoids the prospect of such unfairness without entering the realm of gerrymandering that smaller/different districts would open the door to.

And why not divide Lebanon into 128 districts (1 man – 1 vote) and forget about proportional representation? Imagine the amount of gerrymandering and inequality that our politicians could do while drawing up 128 districts. Another problem is sectarianism: Imagine a constituency that is 45% from the sect A and 55% from the sect B. We all know that on the long-term, A would eventually root for the politician who is endorsing their “rights”, and B would eventually support another politician speaking “in their name”. The idea of a fair electoral law is to end fear, represent everyone and build a society based on mutual trust, not create 128 civil wars instead of one.

And as it happens, the sizes of the districts in terms of registered voters are more or less good. Actually, the biggest three of them, Mount-Lebanon, the Greater North and the Greater South have a number of registered voters that is very close (around 800000). That is also a nice coincidence, because the biggest three of the five constituencies would be allocated a number of MPs that is either identical or extremely close (The different constituencies would be allocated a number of MPs proportional to the size of their registered voters). The details are explained below, but all in all, and according to the 2013 numbers, Mount-Lebanon, the Greater South and the Greater North would get 30 seats each, the Greater Bekaa would get 21 seats, and Greater Beirut would get 17 seats.

- A Fair and Flexible Law

Registered voters and populations tend to change from election to election, and a fair electoral law should adapt to those changes. Before every election, the number of registered voters would be crunched and the number of seats in every district would be allocated in a way that keeps the 128 seats represented in the fairest way possible: If a constituency sees an increase/decrease in the size of its registered voters, the number of seats representing it would change proportionally. For example, according to the 2008 electoral law, the constituencies that make up the Greater South only have a total of 23 seats, while the Greater South should be represented by 30. Beirut, on the other hand, should have 17 seats and is instead allocated 19 under the 2008 law. The list goes on. Not only does this unfairness automatically end with this electoral law proposal, it also ends forever.

- The Highest Christian Influence Since Taef

Now the very first thing any Lebanese would check in any electoral law is the influence the Christians would have after the elections, especially since it is mainly the Christian parties that keep asking to change the electoral law. They always consider themselves underrepresented and judge that they should have a bigger number of MPs. So I crunched the 2013 numbers (you could see for yourselves in the tables below) to see how many MPs the Christian registered voters would bring into parliament. It’s actually a very simple task: You multiply the percentage of Christian registered voters in every constituency by the number of seats automatically allocated to that constituency, and you sum up the numbers you get from the five constituencies. The result was shocking: One would think that bigger constituencies would lower the Christian influence, but it was in fact the opposite: The Christian registered voters bring in 48.5 MPs out of 128 into the parliament, which is actually very close to the proportion of Christian voters in Lebanon. And not only is this electoral proposal fair to both Christians and Muslims, it also provides the highest percentage of MPs elected by Christians since the 1972 elections: In fact, it is widely known that out of all the electoral laws used in Lebanon since 1992, the modified 1960 law (= 2008 law) brought in the maximum number of MPs elected by Christians: 47 (It’s a majority-based law so only districts where the electors are more than 50% Christians should be counted: 2 from Bcharre, 2 from Batroun, 3 from Zgharta, 3 from Koura, 3 from Jbeil, 5 from Keserwan, 8 from the Metn, 6 from Baabda, 5 from Beirut I, 3 from Jezzine, and 7 from Zahle). However, the Christian registered voters in both Zahle (57%) and Baabda (53%) are borderline / less than 60%, and within a couple of years, the Christians could become a minority in both districts: That’s a sudden drop of 13 MPs. Again, the Christians may or may not drop in numbers and with time they could get less influence with this electoral law proposal, but the drop of influence will be much more subtle under this law, and it would remain at all times proportional to their actual number of voters: if the Christian population drops from 53% to 49% in Baabda, it would mean a loss of 6 MPs under the current 2008 law, but under this law proposal, it would mean a loss of 0.3 MPs. So to sum things up, this electoral proposal does not only offer a higher and fairer Christian influence than the 2008 law (according to the 2013 numbers), it also provides a better representation for everyone on the long-term and makes sure that everyone would be equally represented.

- Do Not Panic: The Seats/Sect Allocation Would Remain The Same

Another thing any Lebanese would automatically check in any electoral law proposal is the number of MPs allocated to every sect. This is a very sensitive subject in Lebanon, and it’s by far the primary civil-war material anyone can think of. Perhaps an electoral law where seats aren’t allocated to sects would be the ideal alternative, but then again, we live in Lebanon, and currently keeping the status-quo regarding the sectarian distribution of seats is a requirement to keep all the Lebanese on board. The idea of an electoral law is to let the people know that they are free and safe, not threatened. This is why this electoral proposal – that safeguards the current seat/sect distribution for Lebanon – could be the perfect transition to a secular electoral law in the future. As I will prove afterwards, it forces sectarian parties to run together, gives a chance to smaller / secular ones to win some seats and eventually promotes bipartisanship in Lebanon while discouraging any kind of sectarian incitement. And in the meantime, all the sects will still have their same “sacred” share of seats.

- Automatic Seat-Allocating System

Now the main challenge I faced when designing the concept of this electoral proposal is that it would be very hard to know where to put every seat. For example, we know that Mount-Lebanon deserves 30 MPs (proportional to its registered voters), but how can we know what seats should be included in that district? Do we put 15 Maronite seats there, or 11, or 13? Without an automatic system, politicians could still influence the results by exchanging sect seats from a constituency with another in order to serve their interests and keep their parliamentary blocs as religiously-uniform as possible. This could open the door to another way of gerrymandering and beats the purpose of the law. That issue has bugged me for ages, until I found a way, via the formula below, to get a decimal number of the sect’s seats in every constituency, in the fairest way possible.

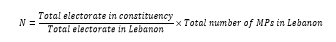

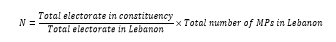

- First, we calculate N. N is the number of seats in every constituency (after rounding up and making sure that the sum of Lebanon’s 5 Ns is 128 MPs).

click to enlarge. The Greater Bekaa’s number of seats (yellow) is 21 and not 22 because while rounding up, I had to remove a seat ( in order to have a total of 128 seats for Lebanon) and the Greater Bekaa’s N has the lowest decimal part above 0.50 (21.54<29.64<29.77<29.96)

- By law, every sect in Lebanon is allocated a certain number of MPs. The trick here is to know how to divide them on the constituencies. So first, we have to find M. M is the number of seats every sect should have in a constituency: We find it by dividing the number of registered voters for that sect in the constituency by the number of registered voters for that sect in Lebanon and then multiplying that result by the number of seats that sect has (by law) in all of Lebanon.

click to enlarge

click to enlarge

- So now we have the number of seats every sect should have in a constituency, but if we add all of the constituency’s seats, we might get a result that is more or less than N. We don’t want that (we want to keep all the constituencies equally represented), so we have to apply a cross-multiplication to make sure that the sum of all seats in that constituency is N. We thus find Z, the decimal number of seats every sect should have in every constituency.

click to enlarge

Voila, the formula that solves Lebanon’s electoral dilemma:

And yes, again, this safeguards the current sectarian representation: 34 Maronite seats, 14 Greek Orthodox seats, 8 Greek Catholic seats, 5 Armenian Orthodox seats, 1 Armenian Catholic seat, 1 Christian minorities seat, 1 Protestant seat, 27 Sunni seats, 27 Shia seats, 8 Druze seats, and 2 Alawi seats. The number of seats and their allocation to the sects would remain the same, and all five constituencies will have an equal representation at all times. All in all, every citizen would have the same voting power (that has never happened in the entire history of Lebanon) and at the same time, the 50/50 Christian-Muslim power sharing agreement would remain unharmed. Everything the formula does can be summed up with the following sentence: Before every election, it automatically redistributes the seats for every sect in every constituency, proportionally to the number of the sect’s registered voters and the constituency’s registered voters in order to prevent politicians from redistributing the seats themselves in a way that suits their interests.

Now the problem with this formula is that it gives a decimal number of MPs, and sometimes a manual work would still be needed to make sure that no sect/constituency would be allocated (by rounding up) a smaller or bigger number of MPs (in the tables below for example, you could see that by rounding up, the Shia sect received 30 MPs instead of 27, while the Protestant one, which is not anywhere near 0.5% in any district, failed to get its only MP). This small task (That I experimentally tried to do, check the yellow/orange cells in the tables below) could be done by an independent electoral commission, and its work would just be to make sure that the representation is accurate for both the sects and the constituencies, the two main priorities being keeping an equal representation for all five constituencies, and keeping the specific number of seats/sect in order to preserve coexistence. The formula does 95% of the work, and the commission just rounds up/adds an MP there – removes another somewhere else in order to make sure that everything is in its correct place.

- Small Parties Will Never Be Forgotten Again

Another beautiful thing about that proposal is that the constituencies are big enough to have a number of seats large enough to let the smaller parties into parliament. Take a party A for example. Suppose that A has support between 5% and 20% in the cazas of Mount-Lebanon. Under our current law, A would never make it to parliament without alliances it perhaps doesn’t want to make with other parties. However, under this electoral proposal, and with at least 12% support throughout Mount-Lebanon and a 5% or even 10% election threshold (the specified minimum percentage of votes required within a particular district in order to obtain seats in the parliament), A would receive 12% of the 30 MPs. That’s 4 MPs for a small party that would have never thought of having representatives in Nejmeh square without giving something else in return to an electoral ally.

- Religiously-Mixed Coalitions and the End of Sectarian Incitement

But what makes this electoral proposal truly awesome are the electoral results. While the constituencies are too large to predict any winning side (without mentioning that proportional representation only complicates predictions), there is a major achievement. I’m going to take the Greater South as an example. In the Greater South, March 14 currently have 2 Sunni MPs from the whole constituency (Saida). However, under this electoral proposal, March 14 could get (random percentages) 10% of the Shia votes and 60% of the non-Shia ones. And since the non-Shia votes are 31% and the Shia ones are 69%, this would mean that March 14 could get 25% of the votes in the Greater South. That’s also 25% of the Shias MPs representing the Greater South. In other words, March 14 would receive 8 MPs for the Greater South, out of which at least the half are Shia. You would also have for example Sunni MPs in Beirut and the North loyal to March 8 (hint: They don’t exist in parliament right now). The Lebanese coalitions will all have MPs of all sects, representing all regions, in all of Lebanon. This is a huge yet very easy step to make towards ending party-based sectarianism.

Oh, and by the way, the Greater South is by far the least religiously-mixed district. Imagine what could happen in the mixed ones. Not one coalition would have a total control on a sect’s MPs, and not one party running alone could get a religiously homogeneous parliamentary bloc. This means that Lebanon would always have its rival coalitions (if they remain in power) heavily present in all regions via many seats. This law forces sectarian parties to ally to one another, and even if they make it to parliament, there is no guarantee that they will have religiously homogeneous blocs. With time, Lebanese parties will learn that sectarian incitement won’t get you anywhere with this electoral proposal, unlike with the current one (for example, in Keserwen that is 99% Maronite, you could have an advantage over your opponents if you only focus on Christian interests and ignore the national ones. Same thing could be said for Deniyeh, or Tyre for example, where one sect forms a majority of votes). However under this proposal, the constituencies are big enough so that not only coalitions become religiously heterogeneous, but that they also lose any interest in sectarian incitement.

And if things get ugly for example, and for some reason Lebanese politics become Christian vs Muslim, you can make sure that a number of Christian MPs will remain to be elected by Christians and Muslims, and that a number of Muslim MPs will also remain to be elected by Christians and Muslims . This electoral law becomes a safety button that defuses the tensions between Lebanon’s sects by bringing into the parliament a huge number of Christian-elected Muslim MPs and Muslim-elected Christian MPs.

- A Quota For Women

Only 4 out of 128 MPs in parliament are currently women, and a quota should definitely be introduced in order to boost their representation in parliament. Only then will our parliament be truly representative of the Lebanese, regardless of their region, sect or gender. All citizens should have an equal voting power, and all citizens should be fairly represented. It shouldn’t be very hard to add a quota to this electoral proposal, especially that it is based on proportional representation.

- Easy Voting Process for the expatriates

It would be very easy to vote and count the votes from abroad. No need for any bureaucratic attempts to hinder the Lebanese citizen’s right to vote everywhere: It should be very simple as there are only five constituencies, and they happen to be historical ones based on the administrative districts of Lebanon. The ballot boxes could be organized into 5 types, one for each constituency, and the votes would be eventually added up to the results of every constituency in Lebanon. The expatriate votes are thus far easier to include in this electoral proposal than most of the other electoral laws or draft laws. Other reforms could also include electronic voting.

- The Numbers That Prove That The Proposal is Fair and Totally Implementable

I tried in the following tables to apply the formula and see if it could work. In the last table, Yellow indicates that a seat was lost (in order to reach the theoretical total). Green means I did not have to modify the rounded up result of the decimal result (the total was the same number as the theoretical total). Orange means that rounding up removed seats for the sects, so I had to re-add them manually to reach the theoretical total. I started adjusting the Muslim seats, then put the Protestant, Armenian Catholic and Minorities seats in Beirut (They have the higher percentage there, and there were three vacant seats there after I adjusted the Muslim representation earlier). Till now, everything worked like charm, but there were still three Maronite seats to allocate, and the three districts that still had a vacant seat were Mount-Lebanon, the Greater North and the Greater South, so I added a Maronite seat in each of those districts. Technically, the seats of the Greater South and Mount-Lebanon should have went to Beirut and the Greater Bekaa (they have a greater decimal part), but that would have given the Bekaa and Beirut an extra MP and made them overrepresented, so I eventually decided to allocate them to the Greater North and Mount-Lebanon. After all, the two districts make up the Maronite heartland, this would have kept the representation as accurate as possible for all other sects, and most importantly, the two priorities were still respected: Equal representation for the five constituencies, and an unharmed total number of seats/sect in Lebanon. The independent commission’s work would have been to make that small decision. Not that hard, is it? Still better than a cabinet allocating seats the way it wants to.

click to enlarge

Final seat distribution, according to the 2013 numbers. click to enlarge

UPDATE

- A lot of the readers asked if the proposal uses preferential voting / open lists (you get to choose in the list what candidate you like the most and in the end, if a list gets 30%, the most liked 30% candidates on that list get the seats) or numbered lists / closed lists (which allows only active members, party officials, or consultants to determine the order of its candidates and gives the general voter no influence at all on the position of the candidates placed on the list). Both could work, preferential voting making the proposal/vote counting a bit more complicated but even more representative (hence the need for electronic voting).

- Another frequent question was about the distribution of seats mechanism for the winning/losing lists. I’ll make the explanation easier and take the Greater South as an example. There are 18 Shia seats, 3 Sunnis seats, 1 Druze seat, 5 Maronite seats, 2 Greek Catholic seats and a Greek Orthodox one. Theoretically, if a party gets 25%, it gets 25% of every “kind of seat”. You can’t divide a seat if there’s only one for every sect, so those go to the winning list (the Greek Orthodox and Druze seats in this case) and the losing list (or lists) compensates by getting more seats from the sect that has the biggest number of seats. This is why a losing list with 25% of the votes would get 25% of the 30 seats: 7.5 => 8 seats, probably 1 Maronite seat (25% of 5 is 1.25%), 1 Sunni seat (25% of 3 is 0.75) and 6 Shiite seats (since 25% of 18 is 4.5 => 5, and you add an MP in order to reach the theoretical total for the constituency which is 8). All that of course would depend on the smaller details of the Law, but that’s the big picture.

- Another inquiry was about the type of the lists. The lists should be complete in order to force the formation of trans-sectarian alliances, or at least so that the sectarian parties start endorsing candidates from other sects.

- Concerning lowering the voting age from 21 to 18, that’s not something an electoral law can change. It needs a constitutional amendment (Article 21: Every Lebanese citizen who has completed his twenty-first year is an elector provided he fulfills the conditions stated by the electoral law.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.